Introduction

However the Brexit crisis is resolved, the resolution opens the possibility of a general election and a Labour government. Whether still a member of the European Union or in some other economic and political arrangement with Europe, the new government would inherit an unbalanced and stagnating economy. Our purpose is to suggest the most important policies the new government might implement.

From the advent of the coalition government in 2010, long before any serious discussion of a referendum on EU membership, the British economy fluctuated between stagnation and recession due to the growth-depressing effect of austerity. If Britain leaves the European Union and that exit has a negative economic effect, it will come atop the stagnation of austerity. In addition to any Brexit effect, many commentators foresee instability in global financial markets.

Thus, a Labour government will find itself in the throes of three economic threats: 1) the certain and debilitating legacy of almost ten years of Tory designed and implemented stagnation; 2) potential recessionary pressures arising from continued uncertainty as Brexit drags on, or a sudden shock if it ends badly; and 3) the possibility of global financial turbulence.

For each of the three there exist policies to mitigate the negative effect on the UK economy. One of the great ideological successes of Conservative governments since 2010 has been to convince people and the media that the performance of our economy reflects the behaviour of markets, over which public policy has limited impact. Rejecting this bogus naturalism will guide the economic management strategy and tactics of a Labour government.

The insight that fiscal and monetary policies have a major impact on the performance of the macroeconomy was a central message of the Keynesian Revolution. Economic downturns and stagnation result from short run failures of demand that typically result from the instability of private investment. As Keynes famously wrote in The General Theory, when business expectations “are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters… enterprise will fade and die”. If the optimism that drives new private investment is not yet dead, it is certainly on life support. A decade of austerity and Brexit uncertainty brought on by a Tory government will leave to a Labour government the task of rejuvenating our economy.

Economic Performance, 2008-2018

Central to the justification of austerity is the doctrine that economic growth arises naturally from the private sector. The doctrine promotes the theoretically suspect argument that fiscal deficits create a barrier to private sector exuberance. Empirical evidence refutes this naturalisation of the growth process.

Over the eight years 2000-2007, the UK economy grew at an annual rate of 2.5% (0.6% quarter on quarter). This eight year average prior to the global crisis of 2008-2010 was lower than the average of almost 3% for the last fifty years of the 20th century. By any reasonable reading of past trends, the potential long-term rate of growth of the UK lies between 2.5 and 3%.

We chose to err on the low side and take the lower limit 2.5% as our benchmark for what the economy could have achieved in the recovery from the 2008-2010 crisis. The benchmark is doubly modest because the recovery would have occurred at a time of severe underutilization of capacity, allowing for several years of expansion at above potential rates.

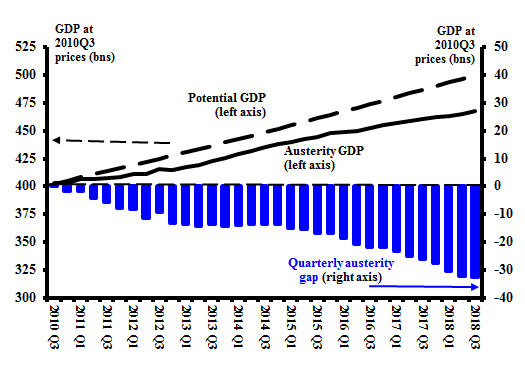

The chart below shows the gap between potential and actual performance during the austerity years after the 2010 general election. The left axis measures GDP at 2010Q3 prices (the first full quarter of the Tory-led Coalition government). The dashed line traces potential GDP, based on the 2000-2007 trend growth rate of 2.5%, while the solid line reports actual performance. The right axis measures the difference between potential and actual.

The diagram conveys a message of massive policy-induced underperformance. By the third quarter of 2018, after eight full years of austerity fiscal policy, the UK economy stagnated at seven percent below its potential. Accumulating the under-performance over those eight years, the total comes to £516 billion – more than the entire GDP achieved for the last quarter in the chart.

This loss of the equivalent of one quarter’s worth of GDP did not result from bad weather, nor from extra holidays due to royal weddings. The loss – £540 billion in current prices, or £8200 per capita – resulted from a conscious policy: austerity. It is not an estimate based on future speculation, nor a guess derived from an assumption-laden model. It comes from actual performance under austerity compared to what the UK economy consistently achieved over the previous 60 years.

Underperformance of the UK Economy, 2010-2018

Policies to Reverse Stagnation

As both circumstances demand and the Labour leadership has committed itself, the first step for a new government is to end austerity. That will prove an easy task.

More difficult will be building on recovery to diversify and balance the UK economy after eight debilitating years.

At the time of writing, we cannot say with any certainty what will be the outcome of the Brexit process following the 2016 referendum. Brexit will make the task of rebuilding the economy more difficult, as there is no Brexit model which does not cause harm to the economy compared to remaining in the EU. This has been shown by the government’s own analysis. The reasons for this are obvious from the most cursory examination – Brexit will reduce or cause friction in trade, additional checks and paperwork will be introduced as standards have to be policed and tariffs collected, the services sector with the EU will decline and investment in the UK by large companies wishing to trade with the EU will be deterred.

On the government’s figures, it is estimated that a Brexit deal based on the 2018 White Paper would cause GDP to be 2-4% smaller in 15 years’ time than it would have been without Brexit.[1] For ‘no deal’, this shortfall is estimated to be either 7.7% or 9.3% of GDP, depending on what happens to migration arrangements. Indeed, it seems that Brexit uncertainty has already depressed our economy; the Centre for European Reform estimates the cost of this up to September 2018 as 2.3% of our GDP.

There are two tasks: enacting a short-term stimulus to bring the economy back up to its potential performance; and implementing a medium-term investment programme to increase that potential. These require different instruments. Ending austerity will prove the simpler task; a new government can achieve it within existing institutions and over a short time period. Following practice well-established in the pre-neoliberal era, current expenditure provides the tool for short-term recovery.

These expenditures are clearly specified in the Labour manifesto for the 2017 general election. Almost by definition, current expenditure can be quickly increased – more funding for the NHS and care services; wage increases for public sector workers with focus on the lowest paid; and increases in transfer payments (“benefits”) through higher unemployment compensation, housing benefits and pensions. Immediately the new government would enhance increased social support payments by phasing out and replacing the disastrous Universal Credit programme.

In the medium term, the proposed National Investment Bank and Strategic Investment Board will provide the vehicle for diversification and balancing the economy. The National Investment Bank, as specified in the Labour manifesto, is the focus of a major PEF event on 7th February at which the Shadow Chancellor will speak.

Conclusion

When economic disaster strikes, government policies can and have in the past acted to moderate the impact and facilitate recovery. Should there be a “Brexit hit”, the same will be true – active management of the macroeconomy can moderate and contain the negative impact. If Brexit is avoided, the task simplifies: reversing austerity in the short-run and implementing a medium- and long-term strategy of rebalancing our economy.

[1] Taking the 50 per cent non-tariff barriers (NTB) sensitivity estimate.