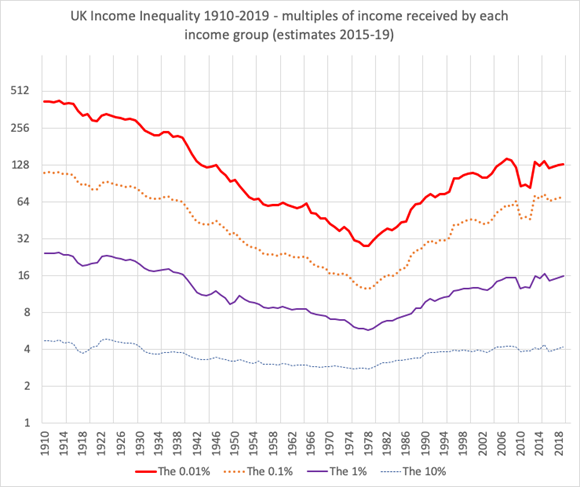

In 1996 a young Tony Blair, Leader of the Labour party, was beginning his campaign to become Prime Minister. In that year the best-off 1% of all people in Britain received 11.9% of all income. This small group included people like Tony Blair himself, but also a very young Jacob Rees-Mogg. Jacob was working in the City of London for a ‘fund manager’ at the time and was a Conservative candidate for a seat he did not win in 1997. Although he did not become an MP, the election of a Labour government in 1997 did little to dent his take. New Labour did many things that were good, but it did not reduce the income gap across the UK. It did not redistribute or significantly increases taxes to curtail greed. The gap rose and people like the young Rees-Mogg, aged just 28 in 1997, in general saw their income grow faster than anyone else and their share of the national wealth spiral upwards.

When Tony Blair was campaigning to win the 2001 general election he had to ignore the fact that the best-off 1% had increased their take to 12.7% of all income. The difference from before, just 0.8%, might not sound like very much, but in 2001 it was the same as the entire average annual salary of someone not in the best-off 10% of British society; with another fifth of their annual income added on for good measure. Imagine that you were one of the best-off 1% of people where you worked and in just five years your annual salary had been raised by the entire annual wage of someone doing a normal job in your workplace! And an extra fifth more ‘to boot’.

The rise in inequality was well deserved, you might say (if you were Jacob). The ‘little people’ should just work harder if they wanted more. If you were in Jacob’s group you were being awarded – each year – 19 times as much money (before tax) as someone outside of the top 10%. You might, understandably, conclude that you were worth at least 19 times as much as those people. After all, why else would you be paid that much money if you were not worth that much? You might resent the taxes you were forced to pay. Jacob was just 32 years old in 2001. He took time off from his fund managing job to campaign to become an MP again, on a platform of reducing his taxes. He lost again.

When Tony Blair was campaigning to win the 2005 general election mutterings of dissent were growing louder amongst his own supporters. However these mostly concerned his war with Iraq. What few people noticed back then was that the 1% had increased their take yet again under New Labour, now to 14.3% of all UK income, to each receive – on average – 22 times as much as the average person in the bottom 90%; the people who most solidly usually voted Labour. The increase in the income of the top 1% between 2000 and 2005 equated to three entire annual salaries of averagely paid people! Inequality between the very top and the rest grew by the most in Tony Blair’s second term as Prime Minister.

New Labour reduced childhood poverty, they quietly installed double glazing into tens of thousands of council houses, they had ensured that a minimum wage became firmly established, they increased education and health funding; but they also allowed the rich to become ever richer and with that resentment grew. The resentment grew as most people found it harder and harder to afford a home. Resentment grew as people were led to believe that it was becoming harder to access health treatment due to immigrants, that the children of immigrants were taking the ‘better’ school places.

Few noticed that as the 1% took more and more they could buy more homes for themselves and to rent most of them out privately. Homes that had previously been social housing or cheaper owner-occupied dwellings (Tony Blair and his wife bought many such homes). Few noticed that as the 1% took more, they could afford to use private health care more and more easily, more often, and so were not concerned that the UK spent less on public health care than almost any other European state. Few noticed that the while the ‘little people’ were squabbling about school places – almost all of the ‘bottom 90%’ who entirely rely on state education – the 1% were almost all educating their children entirely separately and dramatically increasing the amount they spent on their children’s education through ‘rising school fees’.

Jacob Rees-Mogg left his fund manager job in 2007 to form a hedge fund (Somerset Capital Management). Having worked in the City of London for so many years, he may have had a sense that something was up and that the coming year would not be good for conventional bankers and fund managers. The banks crashed in 2008. Gordon Brown later became Prime Minister. He lost the 2010 general election, and for a brief moment, the top 1% saw their share of national income fall to 12.6% in the aftermath of financial chaos, briefly reversing some of the gains they had made between 2001 and 2005 under Blair. Jacob was elected as MP for North East Somerset in 2010 and a coalition government between his party (the Conservatives) and the Liberals was formed.

New Labour did do many good things between 1997 and 2010, but nevertheless income and wealth inequality rose under the stewardship of Blair and Brown. The brief fall that did occur was due to the financial crisis and not government policy. New Labour also, perhaps partly unwittingly, sowed the seeds for greater inequality to come, allowing more of the NHS to be privatized, introducing £1000 a year and then £3000 a year university tuition fees, and introducing academy schools out of local authority control.

By not curbing the growth of inequality, as all previous Labour administrations had done after 1945, 1964, 1966 and 1974, New Labour left office with a majority of the British people, some 90%, having to get by on around 60% of the national income. Contrast that with the rise to 67.7% when the 1945 government left office or, the 71.1% and then 71.2% that Wilson’s governments had left the 90% with, or the 71.6% that the ‘bottom 90%’ received when Labour had last left office in 1979. Without exception, all previous Labour administrations had left Britain a more equal place than when they had taken power. New Labour left it more divided.

When the 2015 election came, the take of the 1% had grown again, to 16.6% or 27 times the average income of average adult in the ‘bottom 90%’. People like Jacob Rees-Mogg and Tony Blair, those with incomes in the top 1%, had seen their take rise by an average addition of 6.5 salaries of those in the bottom 90%! The coalition government had presided over a rapid rise in inequality. Labour elected a different kind of leader that year, Jeremy Corbyn, and radically changed its policy towards no longer tolerating inequality. In the 2017 general election, Labour received an unprecedented upwards swing of support, denying the Conservatives a majority.

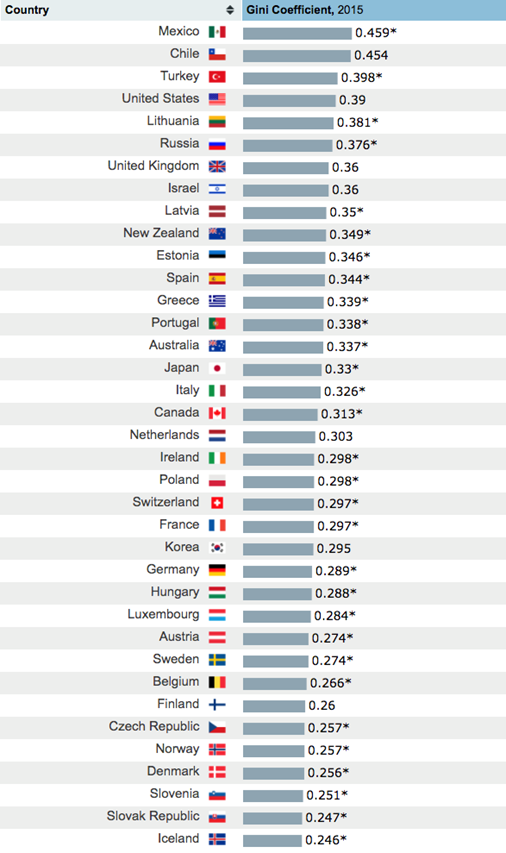

Today Jacob is now the Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council, presiding over meetings of the Privy Council. Inequality has risen, just as he wished and fought so hard to achieve over all those long years. The battle to come is between those who have taken the most. And the rest. For inspiration, Labour will need to look back to what it last achieved in the 1940s, 1960s and 1970s. Labour can also look to what almost all other European countries currently achieve. No other EU-OECD country is as unequal as the UK is today.

The choice today is between becoming more unequal, or more normal. It is as simple as that. New Labour facilitated the rise in inequality. Jacob Rees-Mogg’s type of Conservative aims to accelerate that rise. He and they will do anything they can to prevent inequality falling.

All the sources to the data used in this blog can be found in this book. The fully updated new edition of Inequality and the 1% is out on 17th September 2019.

Photo credit: Flickr/Michael Coghlan.