Since QE was introduced in 2009, it has saved the government over £110bn in interest payments. This is a non-trivial sum, equivalent to nearly 2% of total tax revenue since QE started. For comparison, total NHS spending in 2019/20 was about £150bn. Without QE, the national debt would be at least 5% higher.

The effect of QE on the public finances has attracted less discussion than other possible outcomes, such as increased wealth inequality and higher house prices. This is partly because financing the government is not one of the official reasons that QE was implemented — both the government and the Bank of England are at pains to avoid the impression that QE provides direct financial support to the government. But the fact that it is not much discussed does not mean that it is not happening.

How has QE saved the government so much money? The answer lies, unfortunately, in the technical details. When the government spends more than it receives in taxes – which is almost always – the difference is covered by selling bonds. These are essentially IOUs which entitle the holder to a series of interest payments.

QE involves the Bank of England buying up these bonds. To do so, the Bank issues a different kind of IOU called “reserves” which, ever since the financial crisis of 2008, have paid a very low rate of interest: reserves currently pay interest at 0.1 per cent.

If the government borrows £1bn by issuing bonds at a 2 per cent rate of interest, the Treasury is then obliged to pay £20m per year to the bond holders. If the Bank of England subsequently buys up these bonds, however, overall interest payments made by the government are dramatically reduced to £1m per year. This is because the Bank makes a tidy profit borrowing at 0.1 per cent to lend at 2 per cent and the Bank’s profits – in this case 1.9 per cent of £1bn or £19m – are returned directly to the Bank’s owner: the Treasury!

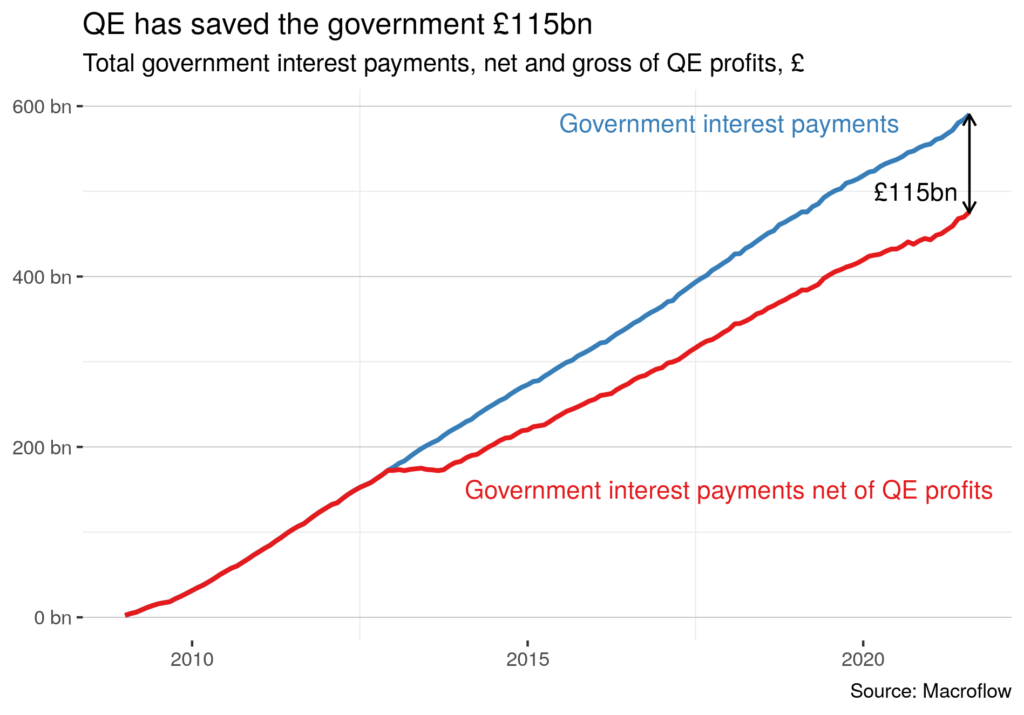

Since 2009, total interest payments paid to the holders of government bonds add up to around £590bn. However, the Bank has bought up a large chunk of these bonds while financing these holdings at much lower rates of interest. As a result, the total sum paid in interest to private bond holders by the Treasury and the Bank combined is substantially lower, at around £475bn. The difference between these two sums tells us how much QE has saved the government in interest payments: around £115bn.

In fact, this number almost certainly understates how much has been saved. This is because, in addition to the direct effects described above, QE also reduces the government’s interest costs in more indirect way. When the Bank buys bonds, it reduces the available supply in the market. This pushes up the price of the bonds remaining in the market which in turn reduces their “yield” (the effective rate of interest). This means that any further borrowing by the government will be at a lower rate of interest than would otherwise have been the case.

These figures illustrate the power of QE in to reduce the interest costs arising from government expenditure. As discussion turns to potential interest rate rises in the face of inflationary pressure, some have argued that QE exposes the government to higher interest costs: as the rate paid on reserves increase from the current low of 0.1 per cent, the “profit” of QE may disappear or even turn negative. But this is not inevitable. By introducing a “tiered reserve” system – some reserves pay the higher Bank rate while a substantial chunk remain at a lower rate – the money-saving power of QE can be retained, even as interest rates rise.