The global economic slowdown is not the outcome of forces beyond human control, but rather an outcome of policy – in particular, of austerity in Europe.

Over the last few weeks, two narratives seemed to dominate the economic news: 1) the gathering economic disaster caused by a feared “no-deal” in Brexit negotiations, and 2) a slowdown in the global economy that threatens recession or worse. To an extent the two narratives pass like ships in the night. The first narrative is presented as the reason of the low growth of the UK economy, while the second is mustered to explain recessions or near-recessions in France and Germany.

What the two narratives share is a strong element of helpless resignation. If “no-deal” transpires, no one can prevent the economic consequences. Similarly a downturn in the global economy arises from quasi-natural causes beyond human agency. Both narratives tend to ignore or deny the principle cause of our economic woes, which predates Brexit by several years and largely accounts for the global slowdown: austerity policies by the governments of most of the G7 countries, whose economies together account for over half of global output.

The implementation of austerity policies in Britain is well known, where central government expenditures have remained approximately constant over the last five years when we adjust for inflation. This constancy hides the severe reduction in local government spending over that time period. So inculcated are the media in austerity ideology that the announcement of a budget surplus as the economy stagnates is reported as good news. In an earlier, more rational era most journalists would have realized that the surplus is one of the causes of the stagnation, a problem not a benefit.

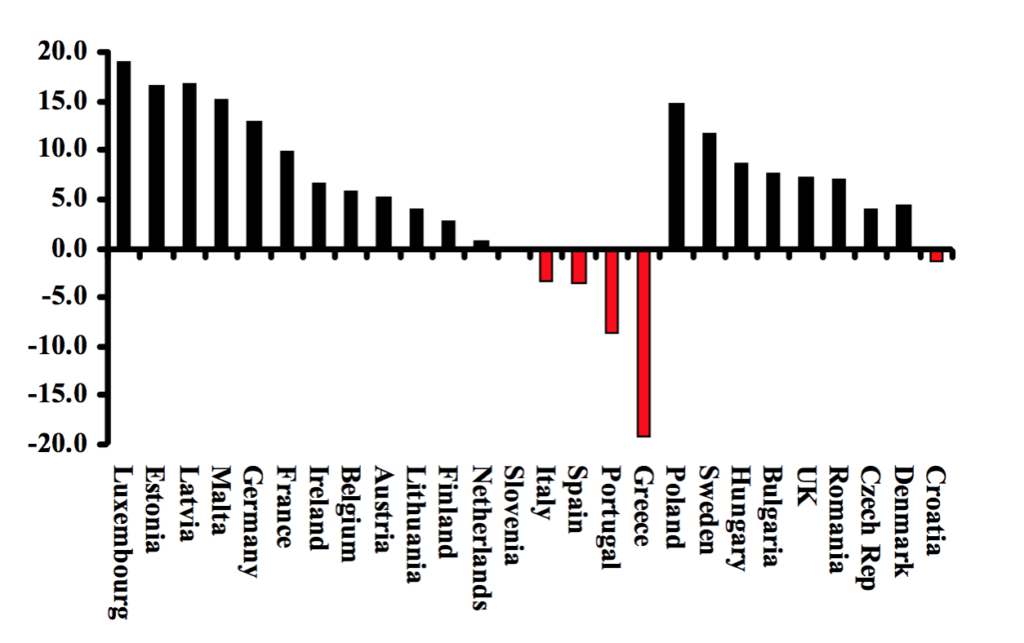

Austerity policies within the EU – especially within the Eurozone – have been more severe than in the UK, as the chart below shows. Aside from the notorious case of Greece, this is not widely known in Britain. The chart shows changes in public expenditure in constant prices for 15 of the countries using the euro (no statistics for Cyprus and the Slovak Republic) and nine EU non-euro countries (including the UK) over the eight years, 2010-2017.

For the eurozone countries, five of the 17 show real expenditure declines. The five with declines include two of the four largest economies in the eurozone, Italy (minus 3.4%) and Spain (minus 3.5%). When we include France and Germany, the simple average for the four largest EU countries was plus 3.5% or 0.5% per year, close to the 17 country euro area average of 0.6%. For the 9 non-euro countries the average was higher, but still quite austere at slightly less than 1% a year.

Government Current Expenditure, 17 Eurozone & 9 non-euro countries, 2017Q2 compared to 2010Q1 (% change, constant euros 2010).

Source: Eurostat. This chart is taken from a report for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation by John Weeks and Jeremy Smith, Economic Guidelines for a Better Union, London: PrimeEconomics, 2018). Note: No statistics for Cyprus and the Slovak Republic.

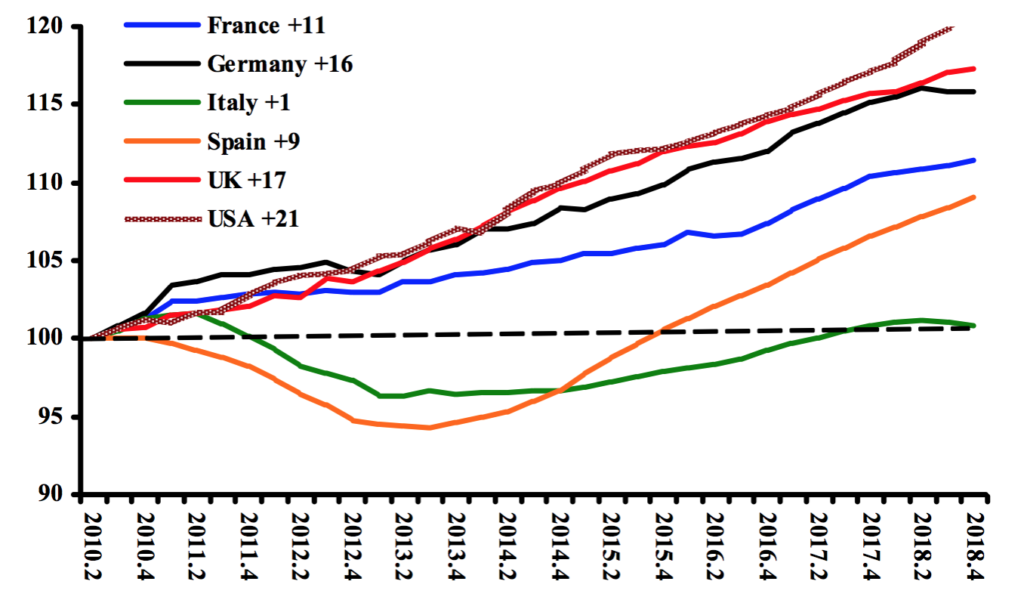

The second chart shows the consequence on economic growth of almost a decade of EU austerity. As the Office of National Statistics documented and PEF Council member Geoff Tily has elaborated, the post-2008 recovery of the UK economy has been the slowest on recorded.

Not withstanding that dismal performance, in the era of fiscal austerity the UK recovery surpassed that of all four of the large euro zone countries. At the end of 2018 the UK reached a meagre 17% above the second quarter of 2010 when George Osborne initiated fiscal austerity. The stumbling German recovery comes a close second at 16%, with France well below at 11%, Spain at 9 and Italy barely qualifying for stagnation at plus one percent. By comparison, the US 21 percent at the end of 2018 appears as prosperity.

Further evidence of the austerity induced stagnation of EU economies comes in trade statistics. Prosperous, growing economies draw in imports and export robustly. Stagnating economies do not. According to Eurostat, during 2010-2017 exports among euro zone countries grew in nominal prices at 3.2% per year, while euro zone exports to non-EU countries grew at 4.3% (Weeks & Smith 2018, 18). That is, exports of the 19 euro countries grew faster with other countries than among themselves.

An obvious inference is that lack of eurozone demand due to fiscal austerity outweighed three well-known benefits of the currency group, 1) use of the same currency brings lower transactions costs; 2) geographical proximity means lower transport costs; and 3) has the much-cited advantage of “frictionless trade”. Fiscal austerity undermined the eurozone as an engine of trade generation, forcing producers to seek more economically robust markets.

Austere Recovery: Index of GDP for 5 European Countries & the US, 2010Q2-2018Q4 (2010Q2= 100). Source OECD.

Domestic politics overwhelmingly determined the outcome of the 2016 referendum on EU membership. However, if after 2010 had the governments of the largest countries chosen expansionary policies and provided a prosperous contrast to the Conservative government’s growth depressing austerity, it might have prompted more citizens to vote Remain.

Why is the world economy slowing down? The reason lies partly in the macroeconomic austerity policies of the European Commission and the major EU countries. By changing policies the slowdown can be reversed. Economic stagnation is a policy issue, not a natural phenomenon.

Photo credit from previous page: Flickr / Des Byrne