The Financial Times front page this morning splashes on reports that China is dropping its studied neutrality over the Russian invasion of Ukraine:

China signalled it was ready to play a role in finding a ceasefire in Ukraine as it “deplored” the outbreak of conflict in its strongest comments yet on the war.

Beijing said it was “extremely concerned about the harm to civilians” in comments that came after a phone call between Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi and his Ukrainian counterpart Dmytro Kuleba.

“Ukraine is willing to strengthen communications with China and looks forward to China playing a role in realising a ceasefire,” the Chinese statement said on Tuesday.

It added that it respected “the territorial integrity of all countries”, without indicating whether Beijing accepted Russia’s claim to the Crimean peninsula or shared its recognition of separatists in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine.

First signs of this emerged a few days ago, as China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs shifted its neutral tone on the conflict to stress the importance of “sovereignty” in comments to foreign journalists.

China’s central role here shows the way in which power in the world has shifted over the last decade. The US, Canada and European countries, later joined by Japan, took exceptional economic measures against Russia over the last week. These have been described as unprecedented in their scope, taking action against oligarchs, banning some Russian banks from using the SWIFT banking service, and imposing restrictions on Bank of Russia, the Russian central bank.

But the real importance of these measures sometimes gets confused. Blocking SWIFT, the interbank messaging system, has been talked up as a deadly blow to the Russian economy. It certainly adds costs and difficulties to doing cross-border business with Russia and for Russian institutions, but it’s not an economic knockout. SWIFT isn’t a payments service – it’s a system designed for banks to communicate with each other about the payments they wish to make. It could be replaced with phone calls or faxes.: a nuisance, but not critical.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JP Morgan, made the same point in interview two days ago:

He said the move to limit Russian access to the Swift banking network might have a lot of workarounds, meaning it wouldn’t alone stop sanctioned parties or others from doing business. The Swift network is the main messaging system banks use around the globe to conduct cross-border transactions. Mr. Dimon said blocking it doesn’t mean alternative messaging systems are blocked as well.

“A sanction says I cannot do business with you,” Mr. Dimon said. “A Swift thing says I can’t use a communication [tool] to do business with you. I can still do business with you.”

Similarly, sanctions against oligarchs and the networks of criminal financing that they use – flowing in vast sums through London and its associated tax havens – will cause difficulty and nuisance, and plausibly could help turn those closest to Putin against him. But it’s in the category of nuisance – potentially serious nuisance – for the mega-rich, rather than a fundamental blow.

Central bank sanctions are decisive

The deadly warhead in the sanctions is the ban on trading Russia’s central bank reserves. The joint communique from the US, Canada and the European powers says:

[W]e commit to imposing restrictive measures that will prevent the Russian Central Bank from deploying its international reserves in ways that undermine the impact of our sanctions.

Russia will be barred from selling its central bank assets on global markets, where those assets are held in a participating country, or are being traded by an institution or an individual in a participating country. This has left Bank of Russia unable to support the rouble by, for instance, selling those assets to buy roubles (as it was doing until the ban came in force).

And it means that many Russians will assume that both their roubles are worth less, and their banks are at risk of collapse, sparking bank runs – as we have seen. The response of the central bank has been to whack up interest rates to 20%, and to impose various restrictions on taking currency and assets out of the country – most recently, it has banned moving more than $10,000 in foreign currency out of Russia.

Central banks are the lynch-pin of a modern economy, defending the stability of the banking system and (therefore) its currency. Control over a central bank gives a hostile power immense leverage. We saw this in the eurozone crisis, when both Ireland in 2010, and Greece in 2015 were threatened with the collapse of their national banking systems by the European Central Bank, if they did not sign up to stringent austerity measures. Both were brought rapidly to heel.

The sanctions being put in place today are an unprecedented economic weapon applied by the joint powers to the Russian economy. The chaos they have produced is all too evident, the rouble falling, for a while, to an all-time low against the rouble. There are suggestions that financial markets across the world are exposed to the risk of default and economic failure in Russia, but of course the people suffering their effects most right now are ordinary Russians. They are the most effective weapon in the joint powers’ economic armory.

Russian defences against economic sanctions

Crucially, however, the sanctions leave assets not held in the joint powers’ currencies, or in their jurisdictions, outside of their scope. The Bank of Russia’s reserves come to $640bn – a veritable war chest that has been built up, very deliberately, over the last decade or so. Russia squeezed its domestic economy and ran huge current account surpluses which, in turn, enable the central bank to acquire these reserves.

But at the same time, Bank of Russia has been getting our of dollar and dollar-denominated assets, precisely in anticipation of something like this ban being applied. It now holds only $bn of US Treasury bills, massively down from the all-time high of $176bn in October 2010.

Jon Sindreu, in the Wall Street Journal, has a breakdown of the Bank’s holdings today, in a piece noting the holes in the sanctions regime:

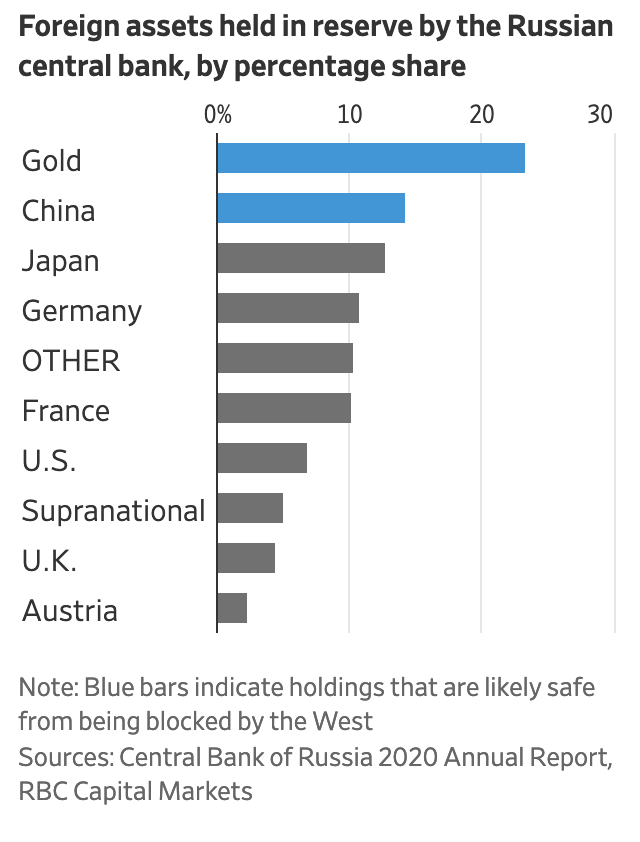

The two largest components are gold and renminbi-denominated assets. As the caption notes, both of these are “likely safe from being blocked by the West”. It’s difficult – arguably increasingly difficult – for even the Federal Reserve to try and bar sales of renminbi assets outside of US financial institutions. Gold, playing the role it has for millennia, is a uniquely tradeable store of value. Russia holds its gold physically inside the country, and – if it can arrange physical transportation, or offer credible guarantees of its future delivery (big ifs!) – this is a viable reserve for exchange.

That leaves China. And this is where the essential leverage of China comes in. Both countries have been building up trade and other economic relations for some time, agreeing a strategic cooperation with “friendship… that has no limits” just ahead of the Beijing Olympics. Since sanctions were imposed on Russia in 2014, trade between the two countries has grown more than 50% and China is now Russia’s biggest export destination. China and Russia agreed a thirty-year contract for gas supplies just ahead of the invasion.

This is a lifeline for Russia right now. But it is also a pressure point, and potentially a decisive one. Europe gets 40% of its natural gas from Russia. This is way the gas trade with Russia is not sanctioned. China’s demand has been growing, but Russia still supplies just 5% of its domestic consumption. China could apply leverage here. Russia’s remaining non-gold central bank assets are renminbi-denominated. China could try to control their use. Or, in both cases, plausibly threaten to do so.

We are a long way from the Cold War: the balance of the world does not hinge on decisions in Moscow and Washington, or even Paris and London. They depend on Beijing.