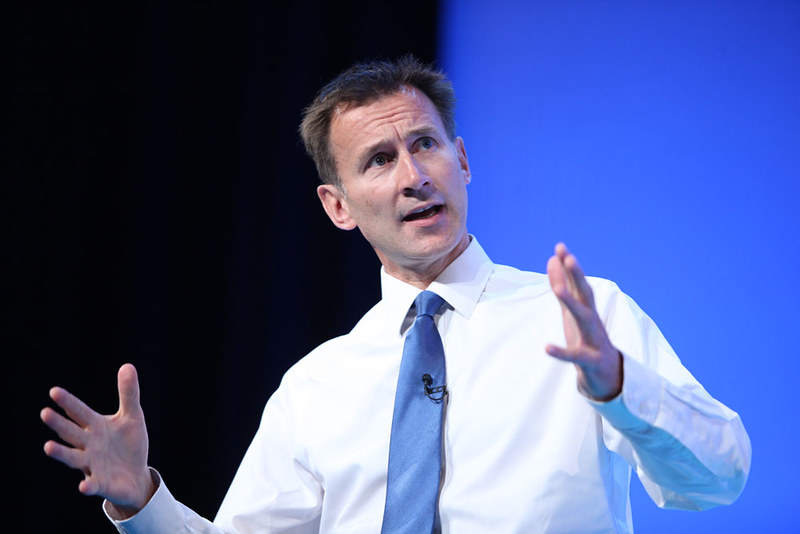

Very interesting report in the Telegraph this morning, seemingly briefed by the Treasury, on Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s thinking ahead of the 31 October fiscal statement, billed by Hunt on Monday last week as the occasion for “eye-watering” cuts. Media reports following duly followed in turn, threatening a return to the bad old days of George Osborne, whose earlier, dramatic cuts did so much damage to the economy and social life.

Yet the Telegraph now tells us:

Jeremy Hunt is considering up to £20 billion of tax rises in the Halloween budget, with high earners to bear the brunt of his quest to balance the books.

The Chancellor has been told by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) that there is still a £40 billion black hole in the nation’s finances, even after he axed almost all of the mini-Budget.

He is looking to raise as much as half that amount from putting up taxes, reducing the need for painful and highly controversial cuts to public spending…

George Osborne, when implementing the austerity measures of the David Cameron years, favoured an 80-20 split of spending cuts to tax rises.

Mr Hunt is believed to feel such cuts are no longer viable, and has had Treasury officials exploring options for a divide as even as 50-50.

The cynical might have suspected some earlier expectations management at work here: without seeing the official Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts, it’s a little hard to judge, but somewhat better than expected growth figures combined with some tweaks to the fiscal rule would clear a fair chunk of the so-called “black hole” in the public finances. (The sacking of Suella Braverman last week appears to have been the product of a row between her and Liz Truss over immigration policy. The OBR model is set up to produce better growth forecasts with higher immigration forecasts – which means if they expect the regime to be looser in future, it would give higher growth forecasts. For example.)

The “black hole” is a product of the forecasts and the government’s own target to shrink the debt. Change the forecasts, change the target, and the black hole shrinks. If Hunt is seriously considering various wealth taxes there are some comparatively low-hanging fruit even for Tories, like the various tweaks the Telegraph suggests to capital gains tax. It wouldn’t be too difficult to remove the “black hole” without the bloodcurdling cuts Hunt has implied are necessary. Filling it becomes even easier if the Tories are prepared to lift taxes on the rich. If the remainder is filled with cuts to capital spending – like new public transport, or energy infrastructure – the immediate impacts of the cuts on most of us will be minimal.

By telling us how bad things are going to get, and then winding back, Hunt and the government can hope to minimise any resistance and win media plaudits for his skilful economic handling. This expectations management.

Don’t be gulled by this. There’s no case for cuts to spending and, after a decade of cuts, very little room where any additional spending can be removed. Cutting back on capital spending, after it has already been whittled away, contributing to the economic weaknesses of the last decade, would be longer-term disaster: we urgently need new capital investment in energy production and low-carbon technology, as well as spending on increasingly essential defences against extreme weather and other climate-related disruptions – like the flood defences foolishly hacked away at in a previous round of austerity. The biggest single “saving” Hunt has so far announced is restricting the Energy Price Guarantee to just six months – meaning, on current forecasts, the typical household will be facing a £4,3000 annual energy bill in April next year as the Guarantee expires.

The government can get through the immediate, short-run crisis with some goosing of the figures and leaning a little more heavily on the wealthy than it has done in the past. It’s a sign of their weakness, relative to the 2010s, and the unpopularity of spending cuts that they have to work like this. But for the longer term – even just for the next few years – we urgently need more spending across the public sector, from investment in renewables to putting health, education and social care back on their feet. Now is the time to raise our expectations, and to demand more from the main political parties, not to tug our forelocks in gratitude that the cuts weren’t quite as bad a kindly Mr Hunt first threatened.