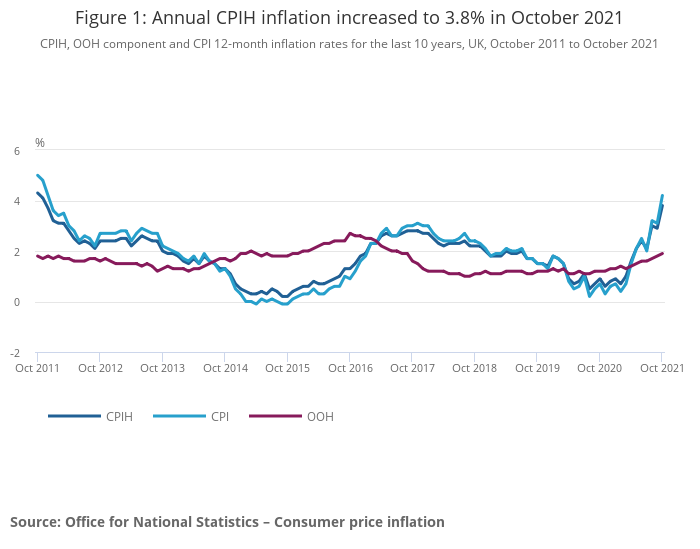

Latest inflation figures from the Office for National Statistics put average price rises in the 12 months to September at 4.2%, its highest rate of growth since November 2011. Back then, a post-financial crisis surge in prices pushed inflation to above 5%, and it stayed high until mid-2014 when OPEC’s decision to maintain oil production helped bring down prices across the globe.

Whilst last year’s lockdowns and subsequent recessions kept inflation very low, as we would expect – with spending falling dramatically, there is little to no pressure to raise prices – reopening since earlier this year has coincided with a dramatic rise in prices. Despite some optimistic claims that this would be “transitory” shift in prices, dependent solely on the unusual demand conditions caused by reopening, nearly 12 months it is harder to sustain the view.

Some of this is due to Brexit, which even prior to Britain’s exit from the EU had pushed domestic inflation up as a result of the fall in the value of the pound, relative to other currencies, after the 2016 referendum. But most of it is from the bigger impact – global, even – of covid-19. Developed countries across the world are seeing similar combinations of supply chain stresses, shortages of key goods, rising energy prices, and higher inflation.

The big question in all this is whether these price rises will fade away as the initial shock of the pandemic wears off – perhaps stretching out into next year, but not much further – or whether they will become entrenched, moving us into a permanently higher inflation regime.

Incorrect models and tighter monetary policy

More conventional Keynesian economists would be far happier with a temporary surge in prices, since the usual belief is that price rises register an economy that is “overheating”: too much demand chasing too little supply and that (therefore) governments should either cut their own spending, raise taxes or, if they are unwilling or unable to do either of those two, to raise interest rates. So persistently high inflation tends to lead to demands for interest rate rises – which, of course, are now starting to happen. Central banks’ own mandates are typically, in this era of their “independence”, modelled on the “Taylor Rule” linking interest rates to inflation, with rates increases mandated as inflation also rises. The Bank of England avoided this temptation at last month’s rate-setting meeting of its Monetary Policy Committee, but the voices demanding a tightening of monetary policy are getting louder.

Latest in this growing chorus is the Financial Times’ widely-read chief economics commentator, Martin Wolf, who sees today the first glimmerings of a return to the 1970s: “as price rises became more general and real wages were being eroded, workers became increasingly militant. Finally, a general wage-price spiral became all too visible.”

Under circumstances where strike numbers in Britain remain close to their lowest since records began, where union membership in the private sector is amongst the lowest in the developed world and – crucially – where average wage growth has been near-zero for a decade, a “general wage-price spiral” should be the last concern anyone has right now. Frankly, a little more “union militancy” would be good for the economy – pay rises would pull back on skyrocketing inequality, and put more money into the hands of people who are more likely to spend it.

But Wolf, instead, sees the problem of pay rises as being one in which inflation can move from being merely “transitory”, driven by exceptional post-lockdown circumstances, and moves into a permanent or at least long-run problem. He cites US economist Jason Furman as noting a tightening of labour markets, with “seven unemployed workers for every 10 openings”. Rattling around in people’s heads is the idea that, if pay rises are won by workers, these will turn into firms putting up prices, causing further demands for wage increases, and so forcing firms to raise prices again, and so on. This is the “wage-price spiral” Wolf refers to.

But the evidence from the last decade is that the British labour market, at least, has not been functioning like this. From mid-2014 onwards, as the OPEC “reverse oil price shock” worked its way through the global economy, inflation has consistently undershot both forecasts and the Bank of England’s own target – and this despite ultra-loose monetary policy of near-zero base rate and huge Quantitative Easing. Austerity, and the public sector wage freeze, certainly played its part, undermining the ability of those seeking work or in employment to bargain for higher pay. But so, too, does the “flexible” labour market, especially after 2010, with its mass creation of deeply insecure, low-paid work like the notorious zero hour contracts.

A model of the economy that didn’t include this extraordinary undermining of labour’s bargaining position – that instead assumed something closer to the labour market institutions of the 1970s were still in place – would be one that persistently overestimates inflation. This happened in the 2010s, and, to the extent that people think a wage-price spiral is a realistic possibility, and blame inflation on it, I think it’s happening again today. And to the extent that this leads to inappropriate calls for monetary policy tightening, it will cause problems today, too.

The real causes of persistent inflation

However, Wolf and others are right to worry about inflation becoming persistent, even if the mechanism they imply isn’t quite there. One part of this is the argument made by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan about demographics: that the exceptionally loose labour markets of the last forty years, the product of two enormous one-time expansions of the global labour force as China and Eastern Europe were integrated into it, are now tightening as this demographic exception approaches retirement. There is no second China out there. There will be no further loosening of labour markets in the future. And so wages, and – in their argument – prices and interest rates will finally start to rise.

It’s an interesting (and intuitive) argument that, incidentally, calls into question some cherished beliefs about the role of central bank “independence” in promoting low inflation over the last two decades or so. And for those with one eye on inequality, it holds out the possibility that the great shift in power towards capital and away from labour that characterised the neoliberal period may finally be coming to an end. This would, of course, over time move us back towards a kind of 1970s world, with higher inflation, higher interest rates – but also, potentially, stronger worker organisation able to win higher pay and better conditions, just like Wolf and others think already exists.

But the other part is significantly less positive. What Wolf calls “special factors”, citing the “surging price of gas” are likely to become less special over time. If there’s a disconnect between some conventional macro modelling and the reality of how labour markets have behaved in the last decade or more, there’s an even bigger disconnect between macro modelling and the reality of environmental decay. As a point of construction, conventional macroeconomic models tend to assume that, whatever is happening today, strong forces in the economy will pull it back to a stable growth path in the long run. But for this to happen, the conditions for growth to occur must themselves be stable. When all our environmental models are saying (for example) that extreme weather events, crop failures and disease outbreaks are all going to become more frequent, the assumption of environmental stability no longer applies.

So if (for another example) there is a frost in Brazil that has damaged coffee production, helping drive its price up to a seven year high today, that is a one-off shock that we would expect to fade away over time – prices would rise once, but the impact on inflation would disappear, since inflation measures price increases over time. But this seemingly one-off, specific environmental shock will be followed by other, similar shocks in the future, most likely at an increasing frequency: more droughts, more frosts, more wildfires and so on. The result will be a sustained increase in costs and prices: or, in other words, higher inflation.

It’s environmental breakdown that we should be worrying today’s inflation hawks, not the possibility of workers winning pay rises. And the prescription for dealing with this kind of ecological ratchet on prices is the exact opposite to the hawk’s usual package: not interest rate rises, but low rates to encourage investment and expand supply – particularly targeting ecological investment, as the People’s Bank of China is now doing. And not panic about rising wages but an insistence that the costs of ecological decline should be borne fairly, with pay increases across the board – paid for out of profits and interest as needed.