As concern over the economic consequences of leaving (or not leaving) the European Union gather and persist, the impact of fiscal austerity on the British economy has tended to recede into the background. While the Progressive Economy Forum shares concerns about the current and future consequences of Brexit, we maintain clear focus on the debilitating effects of fiscal austerity, a budgetary framework initiated in mid-2010 and soon to enter its tenth year.

The important measures of the impact of austerity lie in the suffering of our fellow citizens caused by the termination and reduction of public services. Complementary to human effects, overall measurement provides a revealing summary of what we have lost. The lack of adequate price deflators for public services sets a serious limitation on accurately measuring overall expenditure and expenditure by the various major categories of public services.

Public spending on pensions and health illustrates the measurement ambiguities. The consumer price index provides a generally accepted measure of the purchasing power of the state pension. In the case of health services, “output” is considerably more difficult to measure. A recent Treasury report avoids rather than solves this problem by adjusting every spending category with the general GDP price index. Table 4.2 (p 48) of the report provides a time series for actual expenditure, followed by Table 4.3 (p 49) that gives expenditure in 2017/8 prices.

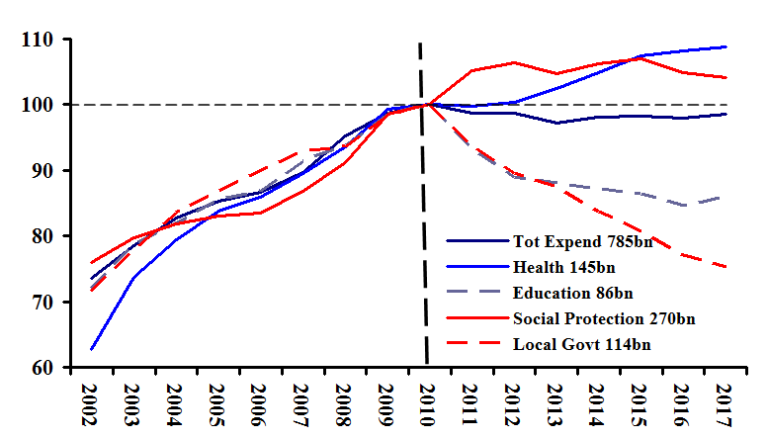

While not methodologically ideal, the Treasury report gives a practical estimate of the “real” value of expenditure, shown in the chart below (“real” is the term the Treasury uses). The chart shows the Treasury’s measures of real expenditures by major category. George Osborn’s emergency budget in mid-2010 resulted in immediate and severe cuts to education and local government. The Treasury numbers indicate that this school year teachers will attempt to educate our children with 15% less funds than in 2010.

The local government cuts were even worse, as central government grants dropped by 25%. As a result, local government spending in 2017/8 fell by fifteen percent compared to 2010. The transfer of business rates to local government revenue represented only a fraction of the loss of central government grants.

Austerity in overall social protection spending began a year after the 2010 election, in 2011 when it had risen 5% above the previous year. After 2011 social protection expenditure hardly changed, constant in real terms for seven years. Only health expenditure shows a steady rise, albeit at a very slow rate. During the seven years leading into the global crisis (2002-2009) real health expenditure grew at 6.5% a year. It increased at 1.3% annually after 2010 or 0.6% per capita.

Central Government Expenditure, 2002/3-2017/8

Source: Her Majesty’s Treasury, Public Spending Statistics 2018, Table 4.3 for all but local government, which is from ONS, Public Sector Finances, deflated by GDP final consumption index. Numbers in legend are actual (nominal) expenditure for fiscal year 2017/8.

The measure of health expenditure in the chart should be interpreted with greater scepticism than for the other categories. A recent ONS study seeks to measure the real quantity of health output. The methodology suggests that considerable inaccuracy may result from the use of the GDP deflator to estimate real expenditure and, therefore, real health service provision. During the eight years of austerity, health services have probably increased, but at a very slow rate, much slower than before 2010. The simply calculated 0.6% real per capita growth is likely the upper limit of changes properly measured.

It is important to stress the extremely slow growth of health spending because it has long run implications. A progressive government could quickly reverse the stagnation in spending on social protection and re-establish the level and quality of programmes within one parliament. To a lesser degree the same is possible for local government services. These are areas in which pre-austerity can be restored through increased current spending.

For the NHS reversing austerity effects will involve a much more difficult task of training new staff, re-initiating research and development programmes abandoned as a result of funding cuts, and re-setting priorities for modernisation never embarked upon. To take a clear example, supporters of free movement of employees correctly celebrate the international diversity of NHS staff. The diversity has a negative side. The austerity period accelerated the practice of seeking cheap staff from abroad rather than investing in training programmes in Britain. The NHS management was in effect contributing to brain drain from countries desperately short of medical staff, where salaries are considerably lower than the low salaries here.

Similar challenges will arise when reversing the disastrous effects of cuts to education. Hiring more teachers, especially when salaries are raised, can quickly reduce student-teacher ratios and deliver basic teaching materials. Reversing the de-modernization of primary and secondary education due to lack of funds will prove more difficult. At the university level de-commercialization only begins with the abolishing of student fees. The entire culture of “value for money” must be replaced with the de-commodifying of university education.

We do not know the consequences of the British government ceasing to be a member of the European Union, only that they are likely to be negative. We know the consequences of fiscal austerity, human misery, opportunities lost and economic stagnation. No referendum, however close its vote, endorsed fiscal austerity. The current government that prolongs the disastrous effects of austerity rules on the basis of having failed to secure a parliamentary majority in the 2017 General Election.

A general election may prove the vehicle to resolve Brexit. It is certainly the route to end austerity.

Photo credit: Flickr / Conservatives