Background to Keynes

Businesses produce things in order to sell them. The implied causality that spending (demand) determines how much is produced (supply) seems so obvious today after 150 years of boom-and-bust that it is strange that mainstream economics largely ignored it from the 1860s into the 1920s.

Ideological bias offers the most plausible explanation of this avoidance of the demand problem endemic to market societies. Before the 1860s the major thinkers from Ricardo to Marx sought to explain the operation of the emerging market system. Whatever their political predilection, they could not ignore the weaknesses of the increasingly dominant capitalist system if they took the task of explanation seriously.

By the 1860s capitalism clearly achieved its dominance, especially in the United Kingdom. The mainstream of the profession adopted as its task justification and defence not explanation. William Stanley Jevons (1835-1882) took the lead in the canonising of capitalism and its value system, an approach challenged only by a few radicals such as John A. Hobson.

For seventy years after Jevons’ seminal work, A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy (1862), a highly ideological model of the market system, prevailed in the profession. That model treated market economies as self-adjusting to full utilization of resources if governments did not interfere with its automatic operation. Competition in unregulated markets would eliminate unemployment and generate the most efficient allocation of society’s resources. The great ills of capitalism, unemployment and inflation, resulted from public intervention and trade unions.

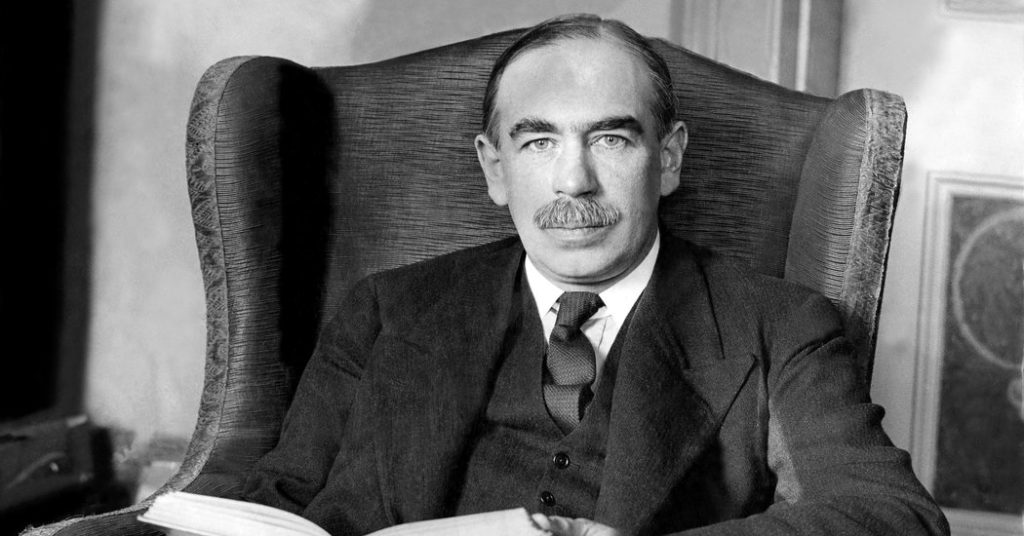

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) referred to this ideology as classical [economic] theory and to its advocates simply as “the Classics” (The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Preface]. While this creates a potential source of confusion (Adam Smith through John Stuart Mill are usually called “classical” economists), in the late 1930s with an article by Sir John Hicks titled “Mr Keynes and the Classics” (1937 established it as standard terminology.

Effective Demand & its Implications

The presumption of automatic adjustment to full employment, continuous full employment, meant that the Classical analysis did not consider changes in the level of output. The economy was always at full employment making it unnecessary to analyze or devote concern to idle labour or machinery.

In his Preface to The General Theory, Keynes makes a criticism of his own work based on this analytical limitation:

“But my lack of emancipation [in the Treatise on Money 1930] from preconceived ideas showed itself in what now seems to me to be the outstanding fault of the theoretical parts of that work…that I failed to deal thoroughly with the effects of changes in the level of output… This book [The General Theory], on the other hand, has evolved into what is primarily a study of the forces which determine changes in the scale of output and employment as a whole; and, whilst it is found that money enters into the economic scheme in an essential and peculiar manner, technical monetary detail falls into the background.” (The General Theory. Preface).

A few sentences later Keynes uses the phrase “a struggle of escape” to describe his intellectual change, “The composition of this book has been for the author a long struggle of escape…a struggle of escape from habitual modes of thought and expression”. It is one thing to recognize that full employment represents a special case, but much more difficult to specify how to explain why employment goes up and down.

After defining his concepts, Keynes provides the insight to understanding levels of output and employment in Book III of The General Theory, “The Propensity to Consume” (Chapters 8-10). In these chapters Keynes verifies the famous quotation by Albert Einstein, “genius is taking the complex and making it simple”, in this case variations in output is the complex and the “consumption function” provides the key to explaining it simply.

We can understand the basic argument without delving into the technical detail of Keynes’ theory of consumption. A market economy has four types of expenditure on domestic products, household spending (consumption), business spending (investment), government outlays and exports. These are obvious and listing them involves no insight. Keynes provided insight by focusing on the two major sources of private domestic spending, consumption and investment.

In this simple case of a purely private economy what households and businesses spend determines what business produce. Business investment creates new production facilities and machinery that may last for years. Therefore, businesses do not make the decision to invest on the current health of the economy, but on their expectations for an extended future (discussed in Chapter 12 of The General Theory). While recessions and depressions discourage investment, as during 2008-2010, investment increases because of optimism about conditions well into the future not just this year. Private investment tends to be volatile and unstable like the expectations that so strongly influence it.

We now come to Keynes’ first major conclusion, that changes in employment and production result from the instability of private investment. When expectations by businesses are robust, the economy expands, driving household spending and raising employment and vice-versa. Household consumption, much of it based on immediate need, tends to be stable compared to investment.

The second major insight follows directly from the first. The amount of private investment determines our economy’s production and employment. While investment and the expenditure it generates stabilize the economy, this can occur at less than full employment. A fully employed economy is the special case, and less than full employment the general case (thus, the title of Keynes’ book, The General Theory)).

Economic Policy Revolutionised

Keynes’ basic insights, that private investment stabilizes output and that stabilization typically occurs with idle labour, constitute the core of the “Keynesian Revolution”. The conclusion that idle labour is the usual state of a market economy has profound implications for mainstream theory and policy.

The insights imply that left to its normal operation, the private sector results in an economy characterized by persistent under-utilization of human and material resource. This leads to the obvious economic policy guideline that public sector intervention is necessary in order for the national economy to maintain and prosper at full utilization of its human resources.

The necessity for policy action to achieve and maintain full capacity forms part of a more general and quite far-reaching conclusion. Mainstream economics is the analysis of, science of some would say, the allocation of scarce resources among unlimited desires. Resources are limited and people’s wants are unlimited. This putative tension between the reality of scarcity and subjective desire for abundance is allegedly resolved through the price system. On the basis of market prices people allocate their limited incomes to best satisfy their wants.

If the normal operation of the economy results in idle labour, then resources are not scarce. Idle labour implies for the economy as a whole more can be produced of everything. To the individual resources appear scarce – household income cannot cover the needs of most families. For the economy in its entirety that opposite is the case, chronic unemployment leaves productive resources wasted. Government spending management converts aggregate idleness into full employment, increasing household incomes and reducing household “scarcity”.

Further reading from PEF economists:

- Geoff Tily, Keynes’s General Theory, the Rate of Interest and Keynesian’ Economics, Keynes Betrayed (Houndsmills: Palgrave 2007).

- Robert Skidelsky, The Essential Keynes (London and New York: Penguin 2016).

- John Weeks, Economics of the 1%: How mainstream economics serves the rich, obscures reality and distorts policy (London: Anthem 2016).