According to an aphorism attributed to Confucius, ‘The easiest way out is through the door. Why do so few use it?’ A modern interpretation is, ‘Do not complicate matters just to distinguish yourself.’

This seemed relevant in reflecting on the Chancellor’s panicky reactions over the past few days. There has never been a budget openly pronounced a failure within three days. To have had three budgets in nine days does not suggest careful planning or preparation for dealing with what was known to be coming for weeks. One can expect more budgets in the next few days. The Chancellor’s inexperience and lack of appropriate qualifications have been glaring. Yet one distinguished journalist has called for him to become Prime Minister.

Be that as it may. Do the measures that have been introduced make economic and social sense? In trying to answer that, full declaration is merited. I write as an economist with ‘green-left’ values. So, I ask of any economic policy: Does it increase or decrease inequality? Is it ecologically sustainable and promote a greener future? And does it distort labour markets or make them more efficient?

One may find that the policies do not do well on those scores, but admit they are better than any alternatives. But at least one should try to answer them.

Take the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, whereby firms with retained regular employees can apply for a grant covering 80% of the average wage up to £2,500 a month, roughly the median wage. The TUC General Secretary, Frances O’Grady, is enthusiastic about this, as are some in the Labour Party.

This scheme deliberately will pay salaried employees not to do the labour they supposedly have been doing. This is the first time a government will pay people on condition that they do not work and do not try to work. I am not sure my economics training prepares me for justifying such a policy.

So, it will pay a firm to lay off workers rather than have them working part-time, and it will pay employees to stop working rather than do part-time labour. It will also pay both firm and employee to claim he or she is not working. Of course, everybody will be honest.

The scheme will lock the economy and labour market in a planning gridlock, impeding the adjustment process that economists of all persuasions favour. Even a huge demand shock requires mobility of factors of production and moves of people from sectors where there is no demand to sectors where there is. This will impede that.

But the most extraordinary feature of this scheme is its distributional design. When the dust settles and the empirical analysis has been done by a host of economists and ‘think tanks’, I predict it will be seen as the most regressive labour market policy of the past century.

An apologist might splutter that it should not be seen in isolation. We will come to that. First, note that someone with a salary of £2,500 per month will, if his employer plays straight, receive £2,000, or £24,000 a year. Someone on £1,000 will receive £800 a month. Someone in the precariat will receive nothing. If that is not organised inequality, then I am a duck.

Those on Universal Credit will be given an extra £80 a month, if they can pass through the conditionality hoops. This means that a median wage earner will get 24 times as much as an unemployed person. But perversely the person receiving the much larger amount must not work, whereas the person with the pittance must do everything he can to obtain work. Again, my economics training has not prepared me for rationalising this.

At the time of writing, there are rumours that in a fourth budget, compensation will be coming for the self-employed and possibly others who are not PAYE employees, beyond what has been done in the form of providing £94.25 in sick pay for those self-employed with minimal savings. Let us hope.

But the scheme will also be incredibly inefficient. Employers must apply, forms must be filled, be checked, and so on. There will be no rush to check the veracity of claims. Not too many questions will be asked. This is not the time to check on corporate honesty. Or so it will be said behind the scenes. Clever accountants will be over-worked. No names – all are as honest as the day is long, aren’t they. One can expect lots of salary adjustments and promotions. Somebody previously paid £1,000 may have a nice pay rise, possibly backdated.

Economists deplore subsidies because they encourage and reward inefficiency as well as resource misallocation. This will be worse than most, because there is little interest in achieving efficiency right now.

So, in the end, we have a regressive, inefficient, distortionary system. The question is whether something more equitable, less inefficient and less distortionary exists. There is.

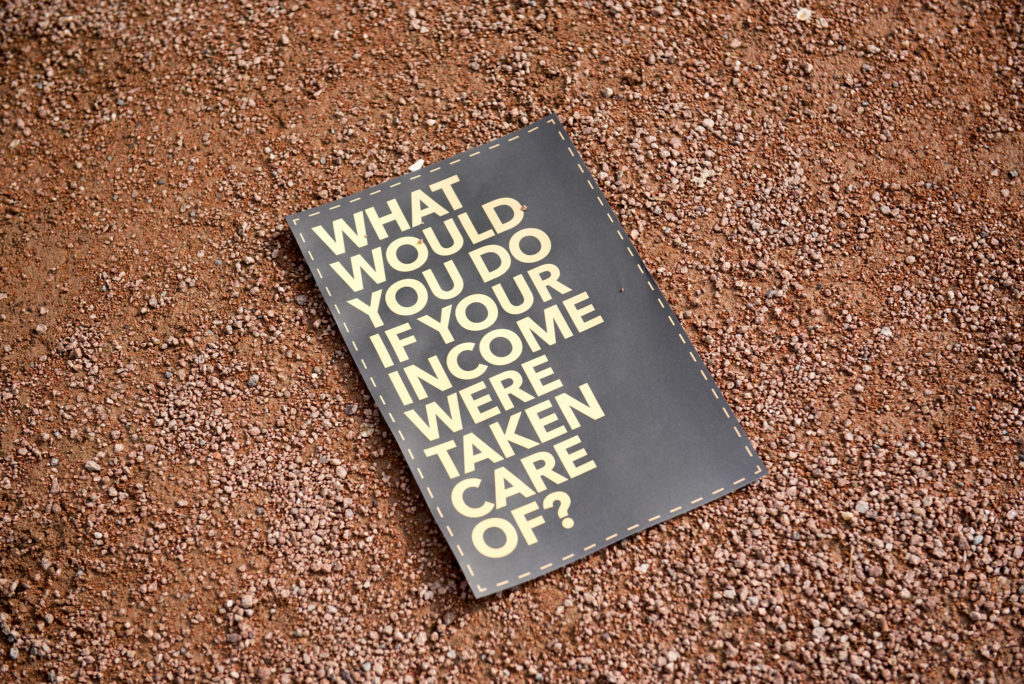

If the same amount of money were used as is likely to be used on the existing measures, the government could pay every legal resident in the country a modest basic income. This would be a stimulus to aggregate demand, and would induce spending on basic goods and services.

This attractive would be more comprehensive than the hotch-potch being put in place. That is vital, since if some groups are not helped, they will become more of a danger not only to themselves but to the whole community, including every reader of this article.

A basic income paid to nearly everyone – I hesitate to say ‘universal’, since for pragmatic reasons non-resident citizens and new migrants would have to be excluded – would have one advantage that does not seem to worry the TUC and Chancellor. It would automatically be progressive, unlike what they favour.

It would also be far less expensive to administer. No application process, no form filling all the time, no checking beyond identification, no checking on payrolls, no adjusting the amount for different groups at different times. This means exclusion errors should be much smaller.

We are not proposing that a basic income replace other benefits. But we must maintain demand for basic goods and services. Unlike current measures, paying a basic income to everybody without requiring anybody to stop working or to resist working would encourage people to spend more time in care work rather than resource-depleting labour or producing public and private bads.

By contrast, what the government is doing is paying people engaged in producing bads while excluding some doing good. Suppose you are an employee in a gambling shop owned by an employer who earned £200 million last year and were paid the median wage of £2,500. While one should not be too moralistic, does it make sense that the government will give a non-working gambling shop employee £2,000, while the three workers doing 8-hour shifts caring for my 95-year-old mother-in-law will receive nothing? A basic income would compensate them equally, and as it would be a higher proportion of the carers’ incomes it would reduce inequality. Some of us think that caring for people at this time is rather valuable.

There is also evidence that paying a basic income would have beneficial feedback effects, helping people keep debts under control, lessening stress that is a major cause of demands on the NHS, and strengthening social solidarity at a time when it is sorely needed. The government, if it were wise, should set up a Basic Income Commission so as to depoliticise what could be a great means of giving us all enhanced resilience that will be vital in the months ahead.

Guy Standing is author of Basic Income: And how we can make it happen (Pelican), and Battling Eight Giants: Basic Income Now (Bloomsbury, March 2020).

Photo credit: Flickr/Generation Grundeinkommen.