During George Osborne’s time as Chancellor of the Exchequer, budgets were typically driven by an ideological commitment to reduce the size of the public sector. This made his budgets rather predictable.

Philip Hammond maintained the rhetoric of balanced budgets, although the tensions within his party resulting from Brexit negotiations constrained and guided his choices.

As the first budget by chancellor Rishi Sunak approaches, media commentators have offered their usual speculation on its likely contents. Across the political spectrum, a pejorative view of fiscal deficits, accompanied by value laden terminology has characterised these commentaries. An article in the Observer refers to the government’s plans to “splash cash” in a “spending spree”, while another in the Financial Times invokes the “black hole” metaphor to describe the mundane possibility of a larger than expected deficit.

The Institute for Fiscal (IFS) studies lent superficial respectability to the predilection for balanced budgets, warning of the need to raise taxes to fund new expenditures. The Resolution Foundation, new on the block with fiscal commentary, ominously warned of “big spending plans” that would create a public sector “bigger than at any time under Tony Blair”, reaching 40% of GDP. This near universal use of negative language to describe desperately needed expenditures indicates the continuing power of the austerity dogma that was so successfully sold to the public by George Osborne in the early 2010s.

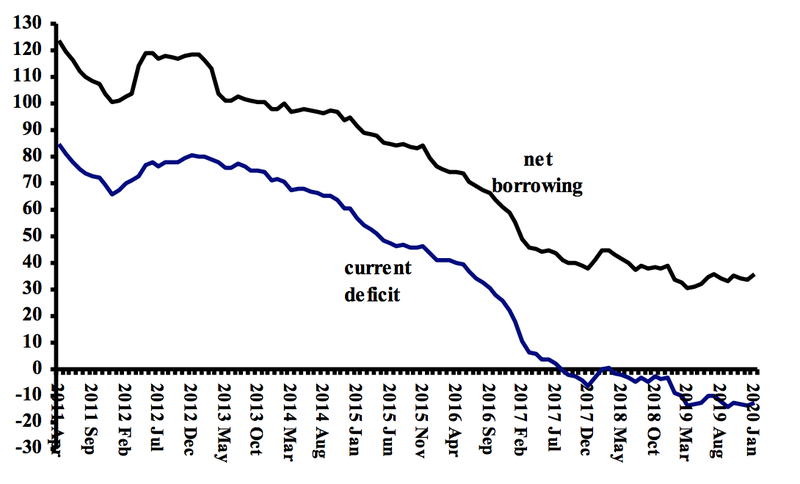

The Tory election manifesto pledged to cover current (“day-to-day”) expenditure with tax revenues, as did the Labour manifesto. The chart below shows that the current budget has been in surplus for more than two years. During the last six months the current budget maintained an annual surplus of close to £15 billion, while public borrowing for investment was a modest 1.4% of GDP.

UK public sector current deficit and net borrowing

In contrast to the fiscal record, the prospects for the economy as a whole appear dire. While the UK economy has expanded slightly faster than the Eurozone since 2013, growth has lagged behind that of the United States. For at least ten years the Chinese economy has driven the world economy, expanding at over 6% per annual for the decade. It is now in imminent danger of recession due in great part to restrictions caused by the Coronavirus.

Contingencies beyond the control of the new chancellor will likely constrain his budget. Foremost among these are economic shocks due to Brexit uncertainty, urgently needed health expenditures resulting from the Coronavirus and a decade of austerity, and infrastructure necessities resulting from long-delayed flood defences.

Spending to deal with a likely healthcare crisis, plus outlays on infrastructure, would provide the fiscal stimulus to counter the demand shocks coming from the global economy. This would seem to be the obvious focus of the this month’s budget.

To oppose or not to oppose?

If the government comes forth with an expansionary budget, as is expected, the opposition will face a problem. In the British tradition the role of the parliamentary opposition is to oppose. This is in contrast to the German system which is characterised by consensus among the major parties since the end of the Second World War. The great advantage of the former is the near absence of backroom deals that remove policy from scrutiny and debate.

The adversarial system is not without its shortcomings. If the opposition aggressively opposes every government policy, nuance is lost. A good example of a missed opportunity for Labour to apply a more nuanced approach came when Prime Minister Boris Johnson forced out his Chancellor Sajid Javid and replaced him with an ally much closer to his views. The mainstream media interpreted Javid’s departure and his replacement by Rishi Sunak as a “power grab” by the Prime Minster, which is undesirable because it weakens the longstanding independence of the Treasury as Britain’s fiscal authority.

According to the Guardian’s Larry Elliot, many former Treasury insiders believe the power grab is “doomed to fail” because of the institutional power and extensive technical expertise of the Treasury. Of prominent commentators only Robert Skidelsky, cross-bench peer and biographer of John Maynard Keynes, positively assessed the move by the Prime Minister.

Though lacking the German Finance Minister’s legal power to veto departmental budgets, the UK chancellor acts as a restraining influence on the spending plans of the government. More than just “first among equals”, the British tradition assigns the chancellor’s the status as the responsible monitor of spendthrift politicians. The chancellor has played this role for generations, long before the austerity era.

As the fiscal authority, the chancellor serves a conservative if not reactionary function that often conflicts with the principles of representative democracy. Treasury “independence” can have no interpretation other than the power to restrain expenditure of the elected government. In effect it institutionalises austerity in the Treasury. To my knowledge no Chancellor has ever asserted Treasury independence by urging for greater spending.

Those enthusiastic about Treasury independence justify it because of an alleged tendency of governments to overspend. In practice the independent chancellor is a milder alternative to proposals for fiscal boards with veto over “excessive expenditures”, as some economists have advocated. As I argue in my new book, this approach treats informed citizens of democratic countries as self-serving and easily bribed by opportunistic politicians.

Looking forward

Progressives should not join the chorus of condemnation of Boris Johnson’s decision to appoint a “chino chancellor” (chancellor-in-name-only), or more bluntly, complain that Rishi Sunak serves as the Prime Minister’s “stooge”. Johnson has moved to undermine the long-standing power of the Treasury. If a Labour government tried to do so, as Harold Wilson attempted in the mid-1960s, it would face strong criticism for abandoning protection against reckless spending.

It may well be that Rishi Sunak should not head the Treasury because of his past business dealings, as the Shadow Chancellor has suggested. But what is considerably more important is that a Tory Prime Minister has initiated a power shift from the Treasury upon which a future progressive government can build.

Whether the motivation is virtuous or venal, when the government acts in the long-run interest of sound economic policy the opposition should distinguish clearly between the essence and appearance of the change.

It may appear that a reckless and duplicitous Prime Minister made a power grab by installing a stooge to head the Treasury. But the essential effect could be quite different; a step towards weakening what Robert Skidelsky has described as “the oldest and most cynical department of government”.

This piece first appeared in Open Democracy, the original post can be found here. Photo credit: Flickr/Number 10.