The Office for National Statistics (ONS) releases a large amount of data at the end of each quarter. On and around Friday 29th March 2019, the day the UK had been destined to leave the EU (but didn’t), many new facts were revealed, but were overshadowed by the furore around Brexit. Twelve of them are listed below.

1. Spending on education in the UK, which includes private school education and university fees, fell by more than spending in any other category other than ‘miscellaneous’. Fewer households can afford private education and there has probably been a slight reduction in the uptake of the offers of places at UK universities. State school education spending has fallen, per child.

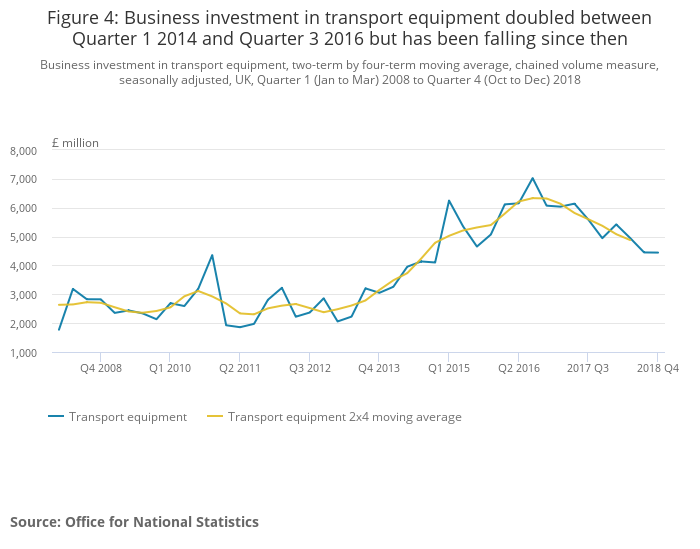

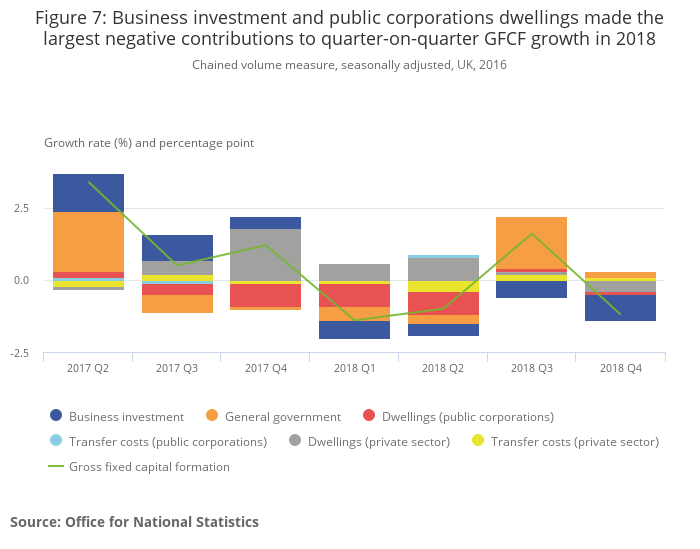

2. Business investment in the UK fell sharply in the fourth quarter of 2019 to become as low as it had last been relative to GDP during the great financial crash of 2008. There were especially large falls in transport investment, down from £7.0bn a year around June 2016 to reach below £4.0bn in 2019.

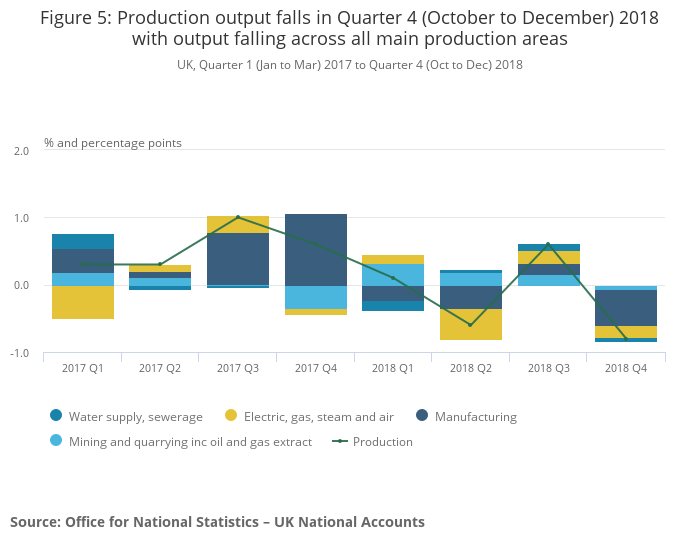

3. By the fourth quarter of 2018, and for the first time in any quarter since at least 2016, productive output in the UK economy fell in all main production areas. This contrasts with overall slow growth before 2016. Recovery from the Great Recession of 2008 had been underway; but the 2010 coalition choice to pursue austerity meant that the recovery was the slowest and shallowest ever recorded. Clearly, the UK is no longer even in mild recovery.

4. The ONS also reported “the fourth consecutive quarter-on-quarter fall in business investment… the first time this has happened since the economic downturn of 2008 to 2009”.

5. On the UK balance of payments, the situation is now awful: “The UK current account deficit widened by £0.7 billion to £23.7 billion in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2018, or 4.4% of gross domestic product (GDP), the largest deficit recorded since Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2016 in both value and percentage of GDP terms.” This particular ONS report went on to highlight the fact that: “UK investors have disinvested in overseas equity securities in the portfolio account throughout 2018, resulting in an overall disinvestment of £174.2 billion in 2018 – the largest on record.” Overseas ‘investment’ was at a maximum during the height of the British Empire.

6. On the economy as a whole: “Real UK gross domestic product (GDP) increased by an unrevised 0.2% in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2018, while the 1.4% increase in 2018 is the weakest annual growth rate since the financial crisis.” This very small growth was only made possible by the UK borrowing more from the rest of the world. The employment rate rose again to a record high of 76.1% with the “unemployment rate falling to 3.9% – its lowest level since January 1975”. The economic woes of the UK are not caused by too few people working. Rather, the work being done is unproductive, the wages being paid are too low, and investment in the UK is drying up – so we depend yet more from the kindness of strangers and borrow.

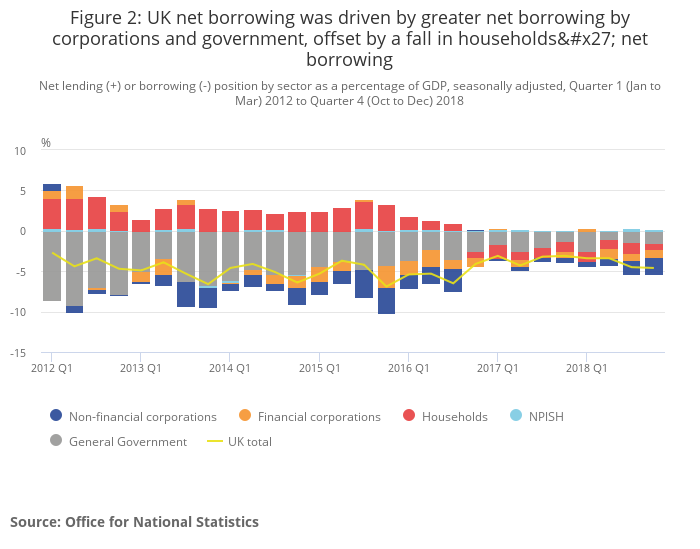

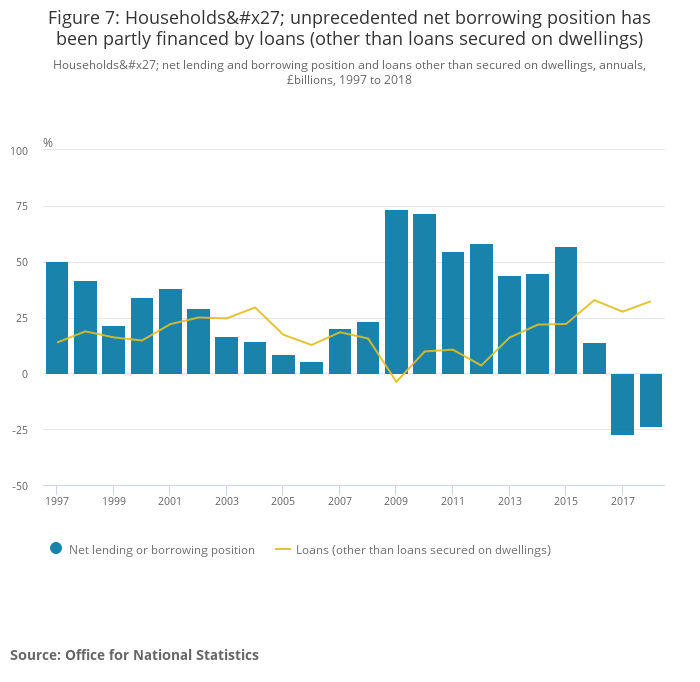

7. The statistics released on March 29th 2019 revealed “an unprecedented ninth consecutive quarter of households being net borrowers, although their net borrowing decreased to 0.8% of GDP from 1.4% in the previous quarter”. The ability of UK households to borrow yet more to make ends meet is drying up. Furthermore, in this release it was revealed that: “Financial corporations experienced an unprecedented sustained fall in net acquisitions of shares issued by the rest of the world in all four quarters of 2018, resulting in the largest annual fall since records began in 1987.” Since the third quarter of 2016 – since the Brexit referendum result – every sector of the economy has been in deficit.

Households in the UK managed to maintain their spending levels during 2017 and throughout 2018 through resorting to unsecured loans in both of these years. The UK is now entering uncharted economic territory.

8. The ONS announced on 29 March 2019 that they will be making “confidential assessments of government and devolved administration policy proposals (as explained in our classification process); we do not announce or discuss such policy proposal assessments as a matter of course in order to afford policy-makers the space to develop policy”. If you do not know what that means – well, you are not supposed to know, and you will not be told what they are doing if you are interested. In that same document the ONS confirmed that they had completed their work on estimating the income the UK government now receives from making visa charges to people travelling to the UK from overseas. These charges have increased substantially in recent years.

9. The income, capital and financial account and balance sheet data for monetary corporations, other intermediaries, auxiliaries, insurance corporations and pension funds were released on March 29th. The seasonally adjusted data show the following levels of gross operating surplus for such UK businesses in the last five quarters (a fall from over £16bn to under £14bn in 15 months).

Gross operating surpluses (selected UK financial businesses)

| 2017 Q4 | £16,127,000,000 |

| 2018 Q1 | £14,412,000,000 |

| 2018 Q2 | £14,293,000,000 |

| 2018 Q3 | £14,015,000,000 |

| 2018 Q4 | £13,877,000,000 |

Source: UK Economic Accounts: sector – financial corporations, ONS. 29/3/2019

10. On 28 March the ONS reported on housing price falls and explained that “The total value of residential property transactions (unadjusted for inflation) decreased most in London in the year ending September 2018.” The UK housing market is in a slump. Transaction levels have collapsed. The price falls are still led by London, where the vast majority of UK housing equity resides. As of 2017, UK banks rely on the value of the homes they have lent on to meet their Basel III stability requirements for minimal capital adequacy.

11. On 27 March the ONS reported that: “Since 2012 to 2014, there have been statistically significant increases in the inequality in Life Expectancy in England for males and females at birth and at age 65 years; the inequality in female Life Expectancy at birth had the largest growth, rising by 0.5 years. In England, the growth in the female inequality came from a statistically significant reduction in Life Expectancy at birth of almost 100 days among females living in the most deprived areas between 2012 to 2014 and 2015 to 2017, together with an increase of 84 days in the least deprived areas.”

12. A day earlier, on 26 March, the ONS released a report showing that a quarter of children aged 11 to 16 (in England, in 2017) with parents “struggling to get on” were living with a mental disorder, as were just under a fifth (19%) of all those children aged 5 to 10. The ONS reported the recent findings of the Children’s Society to help explain this: “Reductions in family income, including benefit cuts, are likely to have wide-ranging negative effects on children’s mental health.” The situation will have worsened during 2018 as reductions to these family incomes continued. We have no idea how the children of the UK will, as a whole, be effected by the events reported above. There is little reason to be optimistic. But, as I write (April 1st), there is still time to avert a hard Brexit.

This piece was originally published in Public Sector Focus here. Photo credit: Flickr / Luc Mercelis.