Ever since the pandemic became unavoidable in the West, some time around spring last year, governments have been attempting to contain SARS-Cov-2 through a combination of exceptional public health measures – lockdowns, social distancing, and travel bans, for example – backed up with exceptional public spending. After a decade of being told by the authorities that there is (to quote the former Prime Minister) “no magic money tree”, suddenly it seems one has been found.

And what extraordinary fruit it has produced. Lockdowns both collapsed economic activity, leading to a sharp fall in the tax take, and, through the demands of furlough expenditure, other benefits increases, and increased health spending, saw government spending increase hugely. Over the last year, the British government spent an additional £280bn last year because of the coronavirus. The deficit (the gap between government spending and taxes) has risen to a peacetime record, and the government debt (the total amount it has borrowed throughout history) has shot up to almost 100% of GDP. Yet the sky has not fallen in: despite a brief wobble in March last year, interest rates on government borrowing have remained very close to the lowest they have been in human history.

There are three reasons the government has been able to fund all of its expenditure. The first is that as a simple technical fact, if a government with its own currency (like Britain with the pound sterling, or the US with the dollar) wants to spend more money, it can do so by issuing currency – the complications emerge after the spending has taken place, not before. As economist Jo Michell has explained, the challenge is that whilst a government with its own currency can ultimately always produce more of the currency as it wishes, and therefore in theory spend whatever amount it wants to, the ability of government to offer (in the UK case) unlimited pounds sterling in payment doesn’t necessarily guarantee the goods and services are available to be paid for. This could result in price rises, as supplier push up prices to meet demand. Or those receiving the new money may decide to use it to buy assets, inflating their prices, or sell the pounds to buy different currencies, pushing the value of the pound down relative to other currencies. In most circumstances, then, governments will find they need to not only decide what spending they wish to make, but also show how the economy’s real resources will be directed towards meeting them.

Borrowing is very cheap

For most governments in the developed world over the decades since the Second World War, making good the gap between what the government spends and what resources it can call on has involved raising taxes, and raising borrowing through government bonds – effectively today a certificate sold to those in financial markets to raise funds, with a promise to repay (usually with interest) later on. A government that can sell these bonds quickly will be in a better position than one which struggles to do so, since a struggling government may well have to offer higher interest rates to lure potential bond-buyers in to the market. Governments that are seen as “safe” by bond traders (that is to say, committed to the interests of bond traders) are likely to face lower interest rates. But since 2008, with some crisis-ridden exceptions like Greece, interest rates demanded by bond traders across the developed world have been exceptionally low. The great fear of the 1990s, of “bond vigilantes” poised to swoop and attack governments not obeying their wishes, does not hold.

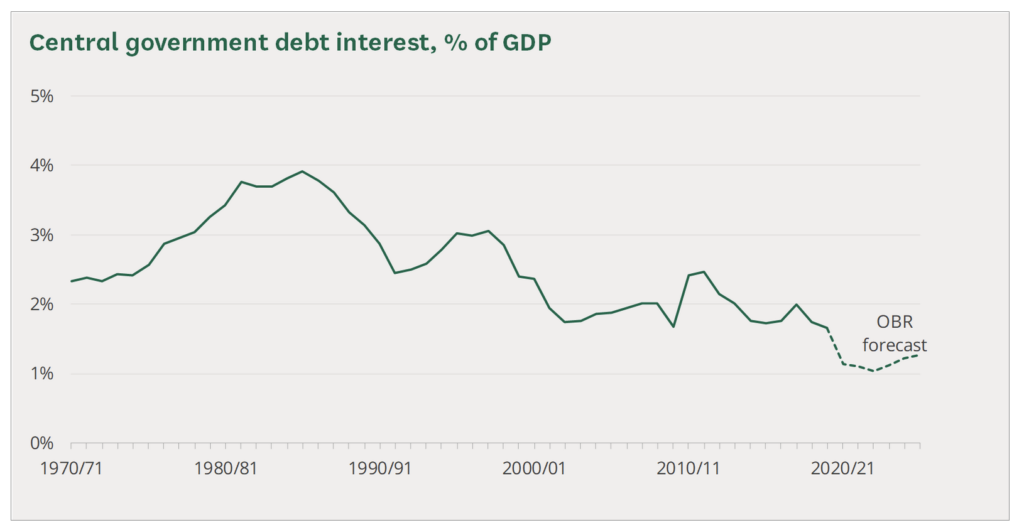

This is the second reason funding has not been a problem: if the British government chooses to borrow, it can do so very cheaply. The graph below is from the House of Commons Library, and shows how much the government has been paying in debt interest, relative to GDP, since 1970. Low interest rates mean that even with exceptional levels of borrowing, the government is paying much less (relative to the size of the economy) in interest than it used to.

The third reason is that this government has continued to rely on the ability of its central bank, the Bank of England, to issue new money as it wishes. This is what “Quantitative Easing” amounts to: for Britain, it is a slightly peculiar process whereby the Bank of England creates new money to buy British government bonds from their current owners – typically major financial institutions like pension funds and banks. But by buying the bonds, and using new money to do so, the Bank is making it far easier for the government to issue bonds now and in the future. The process is a bit more roundabout, since the Bank is buying bonds that are already in circulation, but the effect of the process is to finance government borrowing with new Bank of England money. Over the last year, this has been exceptionally important in keeping government going: government borrowing is £340bn higher than expected in March last year, but the Bank of England had issued £350bn of new money through QE. In other words, the entire cost of government borrowing has been (in effect) financed by QE. The Bank is, as some City investors also believe, very close to “monetising” the government’s debt.

This isn’t a cost-free process: the effects of all that new QE money sloshing around has been to increase asset prices, which in the US has primarily meant rising stock market prices, and in the UK has meant largely rising property prices. This happens because those holding the QE money look for other assets to invest it in, driving up their prices: but the overall impact on inequality is bad, and the effect on the whole economy is to steer more resources into asset ownership, rather than useful spending in the real economy.

But we are simply nowhere near the point at which we should be worrying about the debt, despite its increase. If we were, we might find (for example) that the government was finding selling its bonds difficult. But that isn’t happening. There is a consensus in the economics profession on this point, marking a distinction with the period after 2008 when some prominent economists favoured austerity, but too often we find some politicians and, worse, some senior political journalists repeating nonsense about the government running out of money, or about how concerned we must now be about the debt.

The truth is that we had an exceptional public health emergency to deal with and, like other national emergencies, such as the Second World War, we simply had to spend the money to deal with it. Just as we didn’t panic about repaying the debt as fast as possible after WW2, instead building the NHS and the welfare state, so today we shouldn’t be panicking about it, either. And, looking ahead, it seems likely that much higher public spending will be needed to cope with coronavirus – and meet the demands for improved public services that we are crying out for after a decade of austerity. A sensible balance between some increased taxes on the wealthy – many of whom have done incredibly well financially out of the crisis- and higher government borrowing would take care of this. What we cannot risk, and should give no credence to those calling for it, is another lost decade of spending cuts and austerity.