A cruel irony of modern capitalism is that people in poverty are forced to pay more for many essential products and services. This is what is known as the ‘poverty premium’ – the extra cost of being poor. Poverty is a driver of the poverty premium, and the poverty premium is, in itself, a driver of poverty. It is a vicious cycle that locks people into high costs, debt and having to go without. In the context of austerity, the poverty premium is yet another element of the tsunami of low and stagnant wages, insecure employment and increasing living costs.

What is the poverty premium?

Being poor costs more when the washing machine breaks down and your only option for buying a new one is to approach a payday lender or a rent-to-own company, which can cost up to three times the retail price. This is because you can’t afford to pay up front for a new machine, or are priced out of purchasing contents insurance. And if you manage to get a new appliance, you probably don’t have the best energy tariff as you just don’t have the time to switch providers, meaning that you pay more for your electricity. That’s all before you account for the additional charges incurred for paying monthly and not by direct debit, which is the only way you can manage.

So how many people are we talking about? In the UK there are just over 14 million people in poverty according to Households Below Average Income data and the Social Metrics Commission. The Personal Finance Research Centre at the University of Bristol estimates that nearly three quarters (73%) of people in poverty pay a premium for their energy. That is around 10 million people – or more than 1 in 7 of the UK population – who are forced to pay more because they are poor.

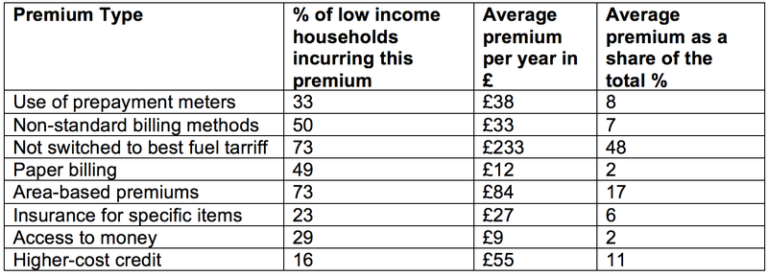

Estimates for the average poverty premium paid annually by low-income consumers range from £256 to £490 a year. The table below shows an estimated breakdown of the poverty premium.

Note: Figures may not sum correctly, due to rounding

Source: University of Bristol

Why does the poverty premium exist?

Firstly, the unfair costs of living. Some people pay a poverty premium if they are considered too risky for, or are excluded from, every day services such as insurance or credit. Is it fair to pay higher insurance premiums because an algorithm has judged a postcode to be ‘high crime’?

Second, the myth of the ‘super consumer’. Very few people have the time or know-how to compare the prices of every product or service that they buy and then switch to better deals. Markets can be complex and overwhelming, particularly for those who struggle to get through each day. Whose problem is this? Is yet ever more competition the answer? Or do businesses, guided by Government and regulators have a responsibility to ensure people in poverty are placed on the cheapest deals by default?

Finally, one size doesn’t fit all. Products and services haven’t been designed with low income consumers in mind. Millions of people are on zero hour contracts, or paid weekly with uneven income levels, meaning they don’t have the money available up front for things like cheaper annual payments. Is it fair that they are charged high levels of interest just to pay on a monthly basis?

How do we get rid of the poverty premium?

The poverty premium has deep rooted causes that can only be solved by bold, structural change. But there are steps that can be taken immediately.

We believe it is vital that Government launches an inquiry into the poverty premium to investigate its causes, its social and human cost, and possible solutions. In addition, an official measure of the poverty premium is needed. We’re therefore pleased that the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has recently released its report on vulnerable consumers. This contained an agreement with other regulators to take forward a feasibility study for a data matching exercise that could lead to a universal empirical measure of the poverty premium.

Regulators need to continue to introduce legislation that minimises the poverty premium, such as the recently-announced price cap in the rent-to-own market. Furthermore, all regulators should commit to hosting incubation hubs, such as the FCA’s sandbox, and to support challenger businesses that are working to reduce the impact of the poverty premium.

Eliminating the poverty premium is an urgent priority, but no one institution can achieve it alone. Government, regulators, and businesses all need to act together to design out the extra costs of being poor, to free millions from its grasp.

This article has also been published on openDemocracy. Photo credit Flickr / Jase Curtis.