Both Boris Johnson and Keir Starmer chose to address the Confederation of British Industry conference this week. But far more interesting than the party leaders’ paeans to profit or to Peppa Pig were the comments made the same day by the CBI’s new Director General, Tony Danker. Greeted with pearl-clutching in the Daily Mail, rentagob Tory backbenchers providing the copy, Danker has taken careful aim at forty years’ worth of neoliberal economic policy in Britain, specifically calling out the loss of manufacturing jobs under successive governments. And although reported as an attack on Thatcher, Danker picked his words more carefully: “Since the 1980s, we let old industries die… We have spent the past decades living with these consequences.”

It’s not something Labour like to talk about, but if deindustiralisation under Thatcher is notorious today – informing, still, how much of the North of England is perceived – its second round, under New Labour, was also far-reaching.

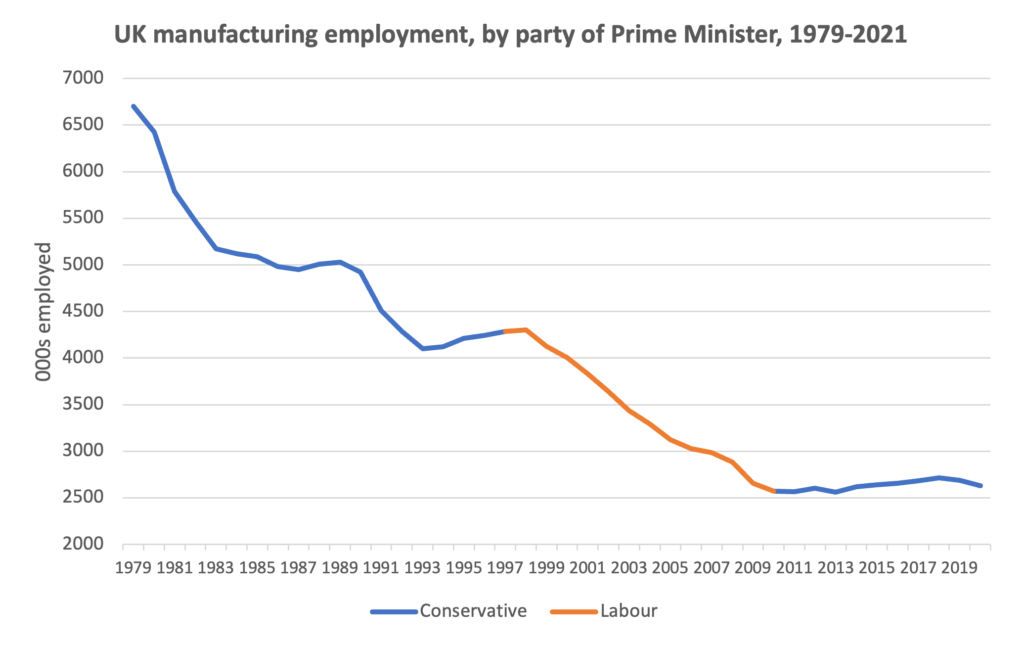

Source: ONS

Between 1979, when Thatcher entered office, and 1990, when she left, employment in manufacturing fell by 1.8m. But then between 1997, when Labour’s Tony Blair became Prime Minister and Gordon Brown’s exit from No.10 in May 2010, manufacturing employment fell by 1.7m.

The only periods of sustained increase in manufacturing employment occurred under Conservative Prime Ministers: rather weakly, rising around 200,000 in the nine years from 2010 to 2019; and then more dramatically under John Major, rising 190,000 in just four years from 1993 to 1997.

Deindustrialisation

The big picture here is well-known: deindustrialisation from the late 1960s onwards was common to the developed world, with major industries, from coal mining to car manufacture, shaking out jobs on a huge scale. Thatcher’s destruction of industrial employment was more dramatic than elsewhere, but not completely out of line with the general experience. The second wave of deindustrialisation in the West, apparent from the mid-1990s onwards but accelerating from the 2000s, then helps account for the loss of jobs under New Labour.

An overvalued pound – itself the symptom of government monetary policy – is common to both experiences, with recovery in employment being particularly tied, in the 1990s, to the crash in the value of the pound following Britain’s exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism.

Of course, under New Labour these lost manufacturing jobs were (in effect) replaced with service sector employment, in both the public and private sectors. Overall employment remained high until the Great Financial Crisis, in striking contrast to the searing rises in unemployment under Thatcher. But the swap of typically better-paid, more secure manufacturing work for typically lower-paid, less secure (private) service sector work was keenly felt and, despite some efforts at geographic redistribution under Labour – whether directly via the old Regional Development Authorities or indirectly via public sector employment – the relative weakening of economies outside of London and the South East became all too apparent once the boom of the 2000s ended.

For the entire period, however, until the last few years, the general direction from government has been consistent: that government itself should, as far as possible, “just get out of the way”. At most, it could compensate for “market failures” in the provision of some essentials – basic infrastructure, say, or education. Labour was more expansive in its spending; the Conservatives, and the Conservative-led Coalition from 2010-15, rather less. When Gordon Brown, as Chancellor the Exchequer, told the CBI conference in 2005 he wanted business regulation to be “not just a light touch but a limited touch”, he was simply repeating the neoliberal commonsense of the time – and no doubt his audience would have nodded along with it.

The contrast with Danker’s argument could not be clearer. Noting the “shot of redemption” new industries give to deindustrialised regions, here he is on making “levelling up” work:

This might be a new line from the head of the CBI, but simply saying the market will fix this is simply not good enough. There are free marketeers in the debate who say government should never play an active role like this. But I don’t know a country in the world – including, and especially, the United States – where governments aren’t active in economic geography.

If we go back far enough we can find heads of the CBI disagreeing with Margaret Thatcher during the early years of neoliberalism. In spring 1981, its then-Director General promised a “bare-knuckle fight” with government over their economic policy. The larger companies the CBI represented were in some “panic” from the 1980 onwards about the impact of mass unemployment and industrial recession on their own profits. Thatcher, for her part, tended to view the CBI at the time as corporatist dinosaurs – bureaucratic managers as responsible for Britain’s presumed decline as the over-mighty trade unions. But for much of the last three decades the CBI has been a reliable defender of the free market doctrine.

It’s a sign of the turn against the neoliberal rules of the game – apparent since the financial crisis, accelerating as the pandemic erupted – that the CBI’s director today will make such a pointed criticism of them, and of how they have failed the last four decades. Would that either main party leader had the same confidence.