UK government figures out today show a 1.5% shrinking in the size of the economy in the first three months of the year – huge by pre-covid standards, but better than was widely expected, with rapid growth in March as schools reopened and some economic life resumed. That last month is likely to be a foretaste for the summer, as the lockdown and social distancing measures are eased through to June.

We know from last year that easing restrictions produces almost an automatic recovery in the economy, as people return to work, and start spending more money. Unlike last year, where a foolhardy government rush to normality helped produce a further surge in cases and subsequent, damaging lockdowns, the vaccine rollout this year has been a dramatic success. Hospitalisations and deaths from covid have fallen sharply, and the sense of uncertainty that hung in the air has reduced. Put all this together, and there is every reason to expect all the main economic indicators – from GDP to employment – to look rosy, right the way through to autumn.

But even this short-term recovery is likely to be highly uneven. The government and the Bank of England have put a great deal of faith in those who have saved money over the last 12 months. Supported by furlough or, more likely, working from home, many have been able to carry on earning during the pandemic, but have had fewer opportunities to spend on anything from restaurant meals to pints in the pub to holidays. As a result, some £160bn of exceptional savings – over and above what people normally save in a year – has built up, nearly all of it simply sitting in bank accounts, waiting to be used. The theory, pushed by the Bank of England, is that with confidence about the future returning, a great deal of this will be taken from those bank accounts and spent in a great rush of pent-up consumer demand. Deutsche Bank are even more optimistic, thinking 10% of the savings pot will be rapidly drawn over this year.

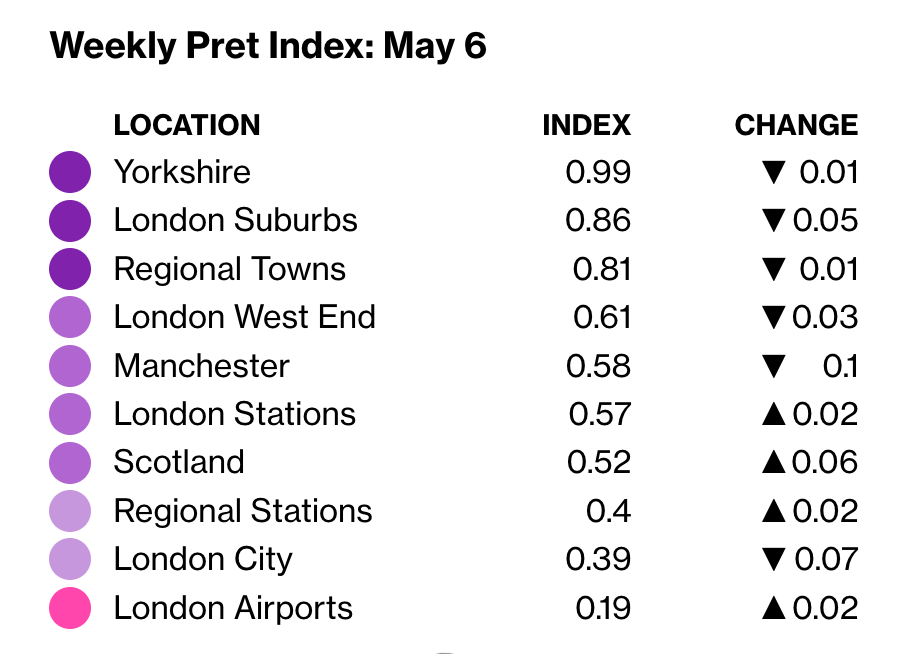

You can argue about the likely scale of this – and the Bank of England’s household survey in November said 70% of households intended to hold to their savings – but the rush to spend itself is likely to cause difficulties. With so much economic activity now shifting permanently online, a surge in consumer spending will not lead to a rapid revival in our high streets in the way it once did. This effect is likely to be reinforced by the shift to working from home, with the BBC reporting that almost all of Britain’s 50 biggest companies anticipate most staff returning to the office a few days a week. But with fewer office workers around, town and city centre shopping will take a hit, as Bloomberg’s new “Pret Index” demonstrates. This shows Pret sandwich sales as a share of January 2020’s figures and, as the table below shows, whilst more rural or suburban locations are almost back to pre-pandemic levels, city centre and transport hubs have been walloped.

This is an acceleration of a major, existing trend, rather than the pandemic introducing something wholly new. A market-led recovery, via consumer spending alone, is likely to leave many (already struggling) high streets. Government support is needed, not least in making sure the 250,000 retail workers that management consultants McKinsey expect to “transition” (nice euphemism) from the sector can find work. Beyond that, however, we need to reconsider what it is our high streets are for. At present we rely on the overspill from commercial activities – you and I going out to shop – to help support the public space they provide. If those commercial activities suffer, the public space suffers. It is time to consider more active government interventions: turning less busy streets into public parks, for example, or providing shared office space and community facilities in disused buildings.

Looking further ahead, we can perhaps already see some of the changes that covid-19 has wrought. With various restrictions on contact likely to remain in place for some time as the virus continues to circulate (and mutate) globally, service business in particular are likely to face significant new costs and uncertainties into the future. Manufacturing, however, is far easier to make covid secure: and, partly as a result, the recovery in manufacturing output and employment has been far more rapid here and (for example) in the US, with the UK Purchasing Managers Index of manufactured goods orders hitting a 27 year high in April. Politically, this is no bad thing for the government, which has set great store in its promises of new manufacturing jobs, particularly in the North and Midlands and particularly in low carbon technologies. But for an economy that remains so heavily skewed towards services, it points to a longer term drag on productivity and growth, once the initial sugar rush of ending lockdown has faded.