In the months before the coronavirus pandemic, the devotion of many mainstream politicians to balanced budgets and austerity was waning. The likes of Germany and the US were looking at improving economic growth through greater government spending, reasoning that central banks were running out of ammunition.

The coronavirus has accelerated this rethink, as shown in a recent Financial Times editorial calling for a new “social contract that benefits everyone”. Such a contract would increase spending to address social inequalities, substantially expanding the public sector.

This fundamental shift in the face of disaster should not surprise us. In 2008, there was much talk of abandoning light-touch banking regulation, though it was later watered down. Will change endure this time?

Wars and spending

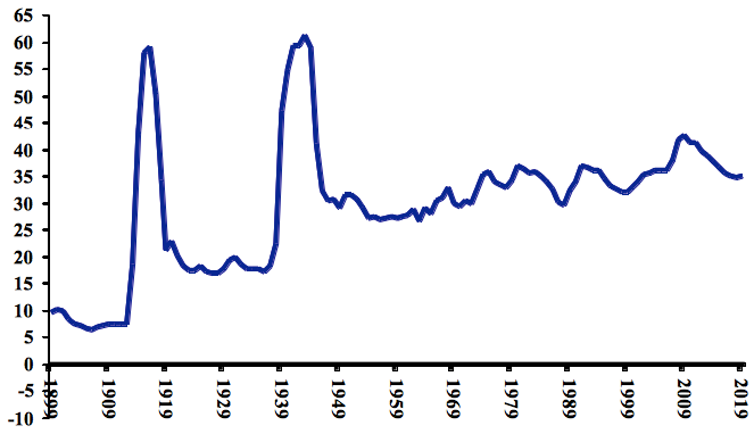

It is worth looking at what happened after the two world wars. In 1913, British government spending was 18.5% of GDP. It rose to 59% in 1916. By 1922 it was back to 18.7%, and essentially remained so for the interwar period.

Public spending as % of GDP

Wartime public expenditure peaked at 61% of GDP in 1945. During the Attlee years it settled into the 30% range – over ten points higher than in 1938 – partly spent establishing the NHS. Even when the Conservatives took over in 1951, spending never again fell below 27% of GDP.

Economic growth differed during these two post-war periods. Between 1919 and 1938, it averaged less than 1% a year. After the second world war, there was a decade of 2.5% annual expansion. Contrasting public spending levels were a crucial difference.

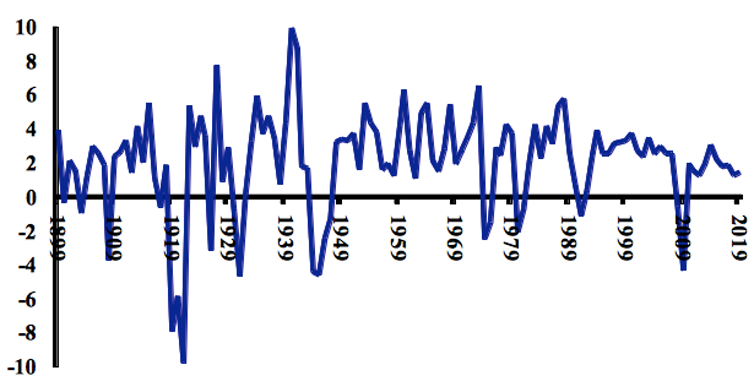

UK GDP growth 1899-2019

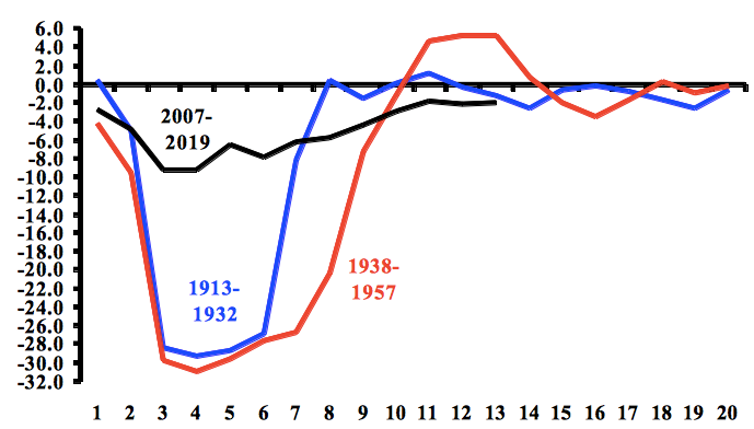

The next chart looks at these periods’ fiscal deficits, meaning government income minus outgoings. Both war-time deficits reached about 30% of GDP then quickly declined, hitting surplus after eight and ten years respectively.

This happened after the first world war, despite the stagnant economy, thanks to a large reduction in military expenditure. Compare the 2007-09 crisis, whose much smaller deficit has endured longer than it took to return to surplus after either war.

Deficits during crises

There are two reasons. There has been nothing to compare to the cuts in military spending. Yet just like after 1918, there has been weaker growth because austerity has depressed demand and business activity.

Where we’re heading

By one recent forecast, GDP for 2020 could fall 15%. Even the government’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicts 13%. If 15% is correct and the 2007-09 collapse is anything to go by, tax revenues might fall 25%. Tax revenues should fall more sharply than GDP because much of the tax system is progressive – for example, no one pays tax on their first £12,500 of annual income, so a 15% drop in the average income will erase more than 15% of the average person’s income tax liability.

By my calculations, a 15% GDP drop plus government recovery spending that I suspect will reach £100 billion will produce a fiscal deficit of 16% of GDP – over £300 billion (the OBR forecasts 14%; several weeks ago, the Institute for Fiscal Studies thought 8% was possible).

Even if the economy quickly returns to 2.5% annual growth, I calculate that public debt will rise to a peak of around 150% of GDP. This is around 50% more debt than the OBR expects, which seems to assume a return to near 2% growth in 2021 without any further recovery spending beyond the initial £70 billion – not tenable in my view.

No doubt some will call for balanced budgets aka more austerity, but I think those favouring increased public spending will probably win out. The UK’s experience after the second world war suggests that such high public deficit and debt levels do not in themselves prevent strong recovery or put an intolerable burden on the state.

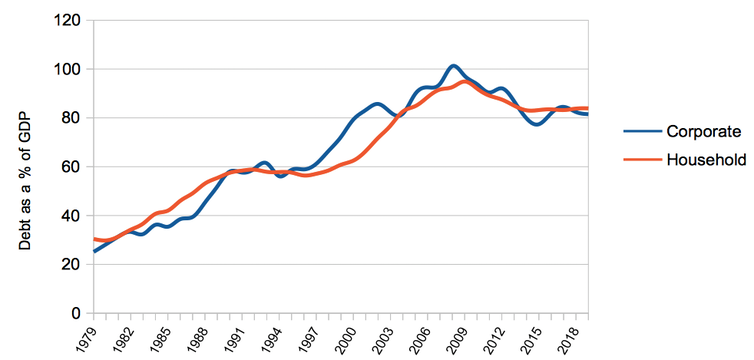

Admittedly recovery could be undermined by household and business debt vastly higher than after the second world war. Both have eased since the 2007-09 crisis, per the chart below, but household debt in particular is rising again – driven this time by credit card and student debt rather than mortgages.

Private debt as % GDP

To achieve sustained recovery, the government might need to have household debt partially cancelled. The chancellor’s recovery programme addresses corporate debt to some extent, by providing businesses with loans with generous payback conditions and other support.

A Tory socialism?

Assuming greater government spending leads to a steady recovery, the ideology of balanced budgets as a continuous policy goal is unlikely to return. But this doesn’t mean the global order will be overhauled. Some commentators predict the end of neoliberalism or a broader resurgence of social-democrat policies, but I think this premature. Both world wars exposed ills in the social system, but only after the second world war did a major shift take place.

Britain will have a Conservative government with a large majority for four more years. The Sun may fear a “Tory socialist state”, but I doubt we’ll see any major expansion of public provision or regulation. Four decades of consumerism have instilled an ideology in many people that taxes are a burden that prevent “freedom of choice” through the market.

For this faith in markets to be swept away, the health crisis might have to lead to shortages of necessities, perhaps linked to disrupted international trade. Perhaps even a Conservative government might then introduce rationing and price controls. But this takes us deep into speculative territory, so we will see how things play out.

This piece is cross-posted from The Conversation

Photo credit: Flickr/Number Ten.