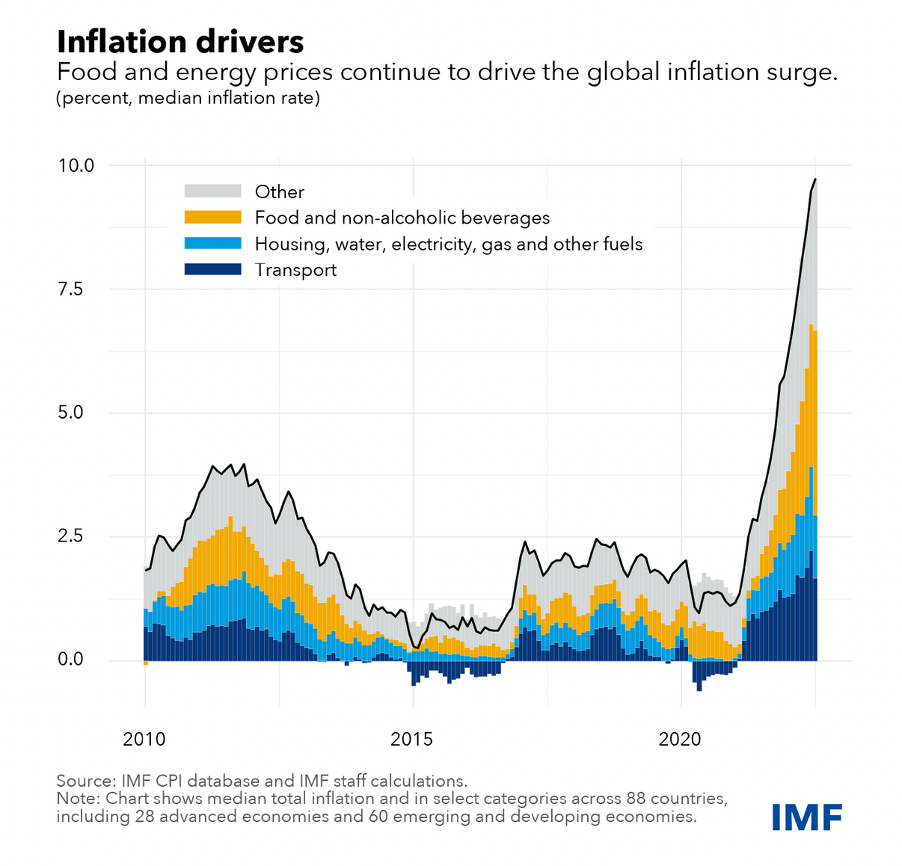

The IMF reports that inflation globally continues to be driven by rises in the price of food and energy:

Food and energy are the main drivers of this inflation… Indeed, since the start of last year, the average contributions just from food exceed the overall average rate of inflation during 2016-2020. In other words, food inflation alone has eroded global living standards at the same rate as inflation of all consumption did in the five years immediately before the pandemic.

They show the breakdown of the contribution of both to global price rises on their “Chart of the Week”, as below:

Whilst inflation in other sectors (the IMF economists pick out service prices in the US) has picked up a little, it is overwhelmingly the impact of price rises in two essentials that is responsible for the rise in prices felt across the world. And because these two are essentials, with few options for substitution in either for most of us – everyone has to eat! – their combined impact on living standards is being keenly felt across the globe.

That squeeze on living standards, in turn, translates into falling sales of non-essential items. As prices for things we pretty well have to buy increases, those on lower incomes across the world – which is to say, almost everyone – are reducing what they spend on things they can choose to buy. If, as in Britain, your household energy bill has gone up £1,000 in the last few months, there are limits to how much you can plausibly reduce that consumption, especially with winter in the Northern Hemisphere approaching. People have been cutting back on expenditure elsewhere – for instance on going out for meals, or Netflix subscriptions. The price rise is, in other words, inducing a fall in demand and therefore pushing economies into recession. The National Institute of Economic Research reports Britain is already in a recession, and the US and other advanced economies are widely expected to follow suit.

This is not, according to the standard model of the macroeconomy, what is supposed to happen, or how inflation is supposed to operate. The standard models depend, critically, on inflation appearing as a result of changes in demand. If total demand for goods and services is pushed above what the economy can supply – if, for instance, the government borrows and spends a great deal of money – inflation will rise as firms chase that additional spending with price rises, rather than expanding output.

But what we can see now is something like the opposite of this process. Rising prices of specific goods and services, where consumption isn’t an option but a necessity, is causing falling demand for other goods and services as consumer shift their expenditure around. Inflation isn’t occurring from demand factors, but from changes to the supply of critical goods and services.

This has important consequences, the most obvious of which is that the usual mechanisms to regulate demand will no longer work, or at least be very limited in their impacts. Raising interest rates, as many central banks are now doing, is intended to dampen demand in an economy, since borrowing becomes more expensive (and saving more desirable). But if inflation is arriving as a result of supply shocks, changing demand won’t do much beyond perhaps pushing up unemployment. For the Bank of England and other central banks to be pushing up interest rates now risks creating “stagflation”: a recession, combined with high rates of inflation.

Traditional demand management no longer effective

The flip side of this is that, if policies to restrict demand have little impact on inflation so, too, do policies that stoke demand up. In the standard model, for the government to propose (as the British government did last week) to borrow around £150bn more than it planned, and to use this as a subsidy to household consumption (in this case, by keeping domestic energy prices lower than they would have been) would normally stoke up inflation a great deal. This time, the expected effect is likely to be exactly the opposite: any extra cash earned by households will simply compensate them for the loss of disposable income from rising energy prices, rather than adding to their earnings. Overall demand will be returned to where it was (almost) without the price hike. And since the spending is intended to cut domestic energy prices, inflation will automatically be reduced as a result – perhaps by around 4%.

The usual rules of “demand management”, in other words, do not apply in a world with idiosyncratic shocks to supply of the kind we’ve been seeing – and will continue to see in the future as the environmental crisis worsens. The implication is that government interventions against the operation of the market are likely to become more, not less, frequent in future. When price spikes are extreme, as we’ve seen in energy prices, they start to call into question the functioning of the market system itself – if the expected 80% rise in UK domestic energy prices had been allowed to go through entirely, the shock to demand in the rest of the economy would have been disastrous. Price controls, once utterly taboo in polite policymaking circles, are coming back into favour as a result.