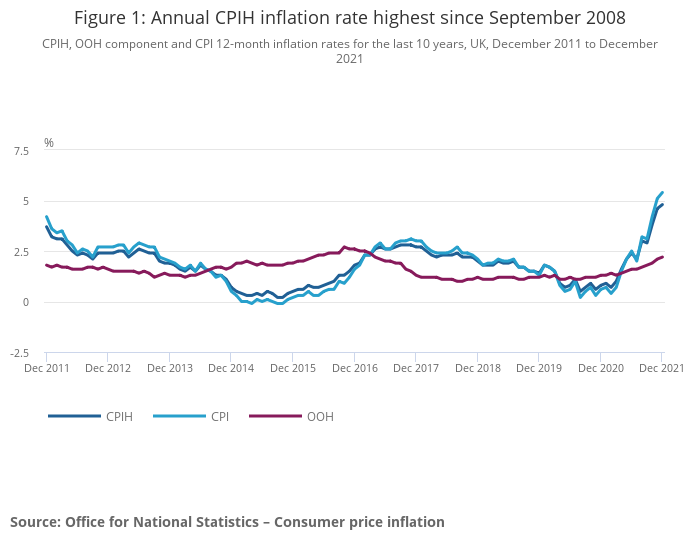

The UK’s official inflation rate has hit 4.8%, up on the previous month and its highest rate since September 2008. Driving the rate are big increases, over the year, in the price of gas and electricity. The largest contribution to the change from last month, however, comes from “food and non-alcoholic beverages”.

Talk over the last year has been about the disruption to the supply of goods services as lockdowns and restrictions hit production and transport, damaging complex supply chains and creating bottlenecks right the way through the system. As economies opened after the initial shock, rapid increases in demand hit these supply chain disruptions, dragging up prices. This is fairly widely accepted amongst economists as an account of why inflation has risen so precipitously, across the world, from early 2021.

But it’s here that the two or three standard stories start to fall apart. For some Keynesians, these supply chain disruptions were only going to be temporary: a rebalancing of the economy, after covid, as the growth restarted. And in the mainstream Keynesian world, if supply was going to quickly expand, increasing demand – for example, by major government spending increases – was nothing to worry about. Many mainstream economists argued that inflation would only be transitory, as a result. They were wrong.

More pessimistic were the monetarists and the believers in “cost-push” inflation. The former, today a somewhat diminished group, argued that the extraordinary increases in the money supply over 2020, as governments used Quantitative Easing (QE) to help ease their economies through the shock of lockdown (and, implicitly, to help pay for their own expanded spending), would inevitably result in rising prices. “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” as Milton Friedman famously argued: he meant that increases in the money supply, more than “real” output increases, would lead to more money chasing the same amount of goods and services, bidding up the prices charged by suppliers. But with QE in operation since 2009 in major developed economies, on a huge scale, inflation over more than a decade in those same developed eocnomies has variously been about as high as today, moderately above zero, and, for a while, actually negative. There is no obvious link between issuing more money and getting more inflation: the causality is not there. Friedman was wrong.

And finally there are those arguing that cost-push inflation would take hold. This depended on the view that rises in a few goods and services would lead to workers demanding more pay to compensate, which would then, in turn, raise costs for businesses and so lead to more price rises. Cost-push could be the mechanism whereby one-off price spikes, caused by the one-off shock of covid, could turn into general and sustained price increases. This isn’t implausible: at the centre of covid’s shock to the economy is its disruption to how work is performed, and one element of that has been the sudden appearance of tight labour markets and at least some workers demanding more pay as a result – or simply walking off their job in the “Great Resignation”. But labour markets overall, although disrupted in peculiar new ways by covid, are not showing much sign of general wage increases: with inflation rising, the opposite has kicked in, with real wages on average now falling behind price rises. Plausibly, this could change in the future, if pay demands pick up. But we are not there yet and, after a decade of flat or even falling real wages for most people, rising wages today should be the least of anyone’s economic concerns. It’s high time workers took a bigger slice of the pie.

Environmental shocks as a driver for inflation

Instead, as I’ve argued before, I think we are seeing the first years of a new form of inflation, one unknown, I’d suggest, in the years since World War Two when inflation became a general phenomenon in the developed world. (Prior to this point, prices had tended to track the general economic activity – rising in booms and falling in slumps. After WW2, inflation became pretty much continual.) It is price rises driven by successive, seemingly idiosyncratic shocks that have arisen as a result of environmental instability. Covid is the most obvious example of this; if we think of the virus as a disruption to the environment that economic activity takes place in, we can see it has acted as an enormous ecological supply shock – and one whose impacts are unlikely to fade any time soon. But in the same way we can see that (for example) the extreme weather events that have disrupted coffee or wheat production, or semiconductor manufacturing, are also smaller-scale examples of this kind of ecological shock. Each one seems idiosyncratic – some unique event disrupting production at some point in time. They’re nearly always reported like this, as CNN do here for disruption to coffee production – as just another extreme weather event that will fade away and allow normality to return.

But of course we know “normality” isn’t coming back. All the environmental modelling tells us extreme weather – along with desertification and greater constraints on food production – will worsen over time, as the climate rapidly changes. That means we should stop thinking about this or that extreme weather shock as a one-off disruption to production, whose impact will eventually wash out of the system, and as simply one more shock in an environment that produces them at an increasing rate. Prices rise as a result of one shock and then, as that impact fades away, another flood or drought occurs, disrupting prices of some other good or service. Taken in total, the overall impact is to force up prices: inflation remains permanently higher on average, but most likely more volatile, as result.

The existing mainstream models don’t deal with this. Putting up interest rates isn’t going to put out wildfires. (Indeed by making investment more expensive, and so restricting future supply, over the longer term higher interests could actively make inflation of this kind worse.) The best responses involve both building in more resilience to supply – removing just-in-time methods and creating more slack in the system overall. But also, if we have a concern for social justice, attempting to spread the costs of these shocks more evenly, leaning them towards the broadest shoulders. That would mean pay rises for most of those in work and more comprehensive insurance for those not in work – preferably as a form of Universal Basic Income.

And if idiosyncratic shocks are driving general price rises, there is a solid case for specific and selective controls on prices subject to shocks, redistributing the cost of those rises. Interestingly, the UK government appears to be looking at one such mechanism, intended to regulate household gas prices when the wholesale gas price spikes. Their plans are (inevitably) geared towards trying to protect company profits – thus exposing taxpayers to more risk than is needed – but at least in principle the idea of price regulation and social insurance against shocks is a good one to think about.